Winning Warsaw: Poland’s Paternalism Hosts UNFCCC Negotiations

BY CAITLIN LEE

At the opening ceremony of the 19th Conference of the Parties (COP19) as part of the United Nations Framework Climate Change Convention (UNFCCC) in November, Hanna Gronkeiwicz-Waltz, Mayor of Warsaw, introduced a short video produced for the Polish Ministry of the Environment to rally UN delegates to “win the Warsaw opportunity” by making considerable progress on international climate negotiations during the two-week climate summit. The video began with Polish school children asking their teacher for a story about their “other Poland” pen pals. The other Poland is later revealed as the village of Poland on Kiritimati Island.

Kiritimati Island is part of The Republic of Kiribati (pronounced KIRR-i-bas), an island nation in the central Pacific Ocean, near the Marshall Islands, Fiji and Western Samoa. Made up of 32 low-lying coral atolls and one solitary island, Kiribati is one of the first nations in the world expected to be lost to climate change-induced sea level rise, and it is estimated that Kiribati may be uninhabitable by the 2050s due to salinization. The warming ocean has caused severe coral bleaching, which has reduced the availability of fish, the main source of protein for the Kiribati people. Kiribati, considered a least developed country (LDC), is one of the poorest countries in the world, and it faces a potential loss of up to a third of its GDP by 2050 and forced migration of its population if serious climate change adaptation does not occur. Despite contributing the second fewest emissions of any nation to climate change, Kiribati has been pioneering against the effects of a changing climate without supportive action from large international powers. In an effort to unite the voices of Small Island Developing States on climate change, Kiribati is a member of the Alliance of Small Island States (“AOSIS”), an intergovernmental organization of low-lying coastal and small island countries.

Unfortunately, none of these facts are explained in the video. Instead, Western Poland paternalistically presents the Republic of Kiribati as a “child victim” in the video, thereby normalizing and validating the developed countries’ use of an oppressive savior-complex as a strategy to evade proactive, binding climate change negotiation, reinforcing international climate negotiation dichotomies.

The video introduces the “other Poland” through its circumstantial name. By doing so, the country of Poland appropriates the village of Poland without explanation. In fact, Poland, Kiribati was named after a European Pole who increased agricultural yield on the island after implementing a new irrigation system. The use of the Poland/other Poland link sensationalizes the relationship between Kiribati and Poland around wordplay rather than discussing the contemporary binary the countries represent. Instead, the divisive developed/developing binary is still often used in the international climate debate and is a more direct reference to the historical and current inequities between countries like Poland and Kiribati.

The developed/developing binary distinguishes countries that industrialized at the cost of the world ecosystem from countries that disproportionately face climate threats despite their lack of participation in changing the climate. This colonial dynamic of profiting at the expense of others is representative of the relationship–past and present–between Poland and the “other Poland.” Although used casually, these binaries exemplify a tense dynamic present at COP.

However, examples of emerging developing countries like China, India, and Brazil, who traditionally have been “the victims” of this dichotomy, complicate the developing/developed relationship. Representative of a transition phase, these nations are currently industrializing at the expense of the climate. In past COP meetings, countries (both developed and developing) have taken advantage of this shift in power structure, evading responsibility and commitment.

This developed/developing dichotomy spun as savior/saved allows for a simplification of the relationship between developed/developing and an alternative justification for aid. The video presumes that if only developing countries are at risk, then developed countries should act out of charity, not out of necessity. Developed countries, knowingly or unknowingly, use this as a tactic to promote their own superiority as a savior of those in need and to discount their own vulnerability, which should be accompanied by a need to take responsibility and act to reverse the consequences of their emissions.

The video emphasizes the relation between Poland and the other Poland through their distant geographies, as the video’s viewpoint zooms out and then pans around a globe, zooming back in to the Republic of Kiribati where a group of children are dancing and singing in a schoolroom. The teacher enters the room of students telling them that their schedule has been changed to incorporate the pen-pal letters. Where children in the Polish classroom have agency to ask for a change in their daily curriculum in order learn about an “exotic” culture different from their own, the children in the Kiribati classroom are not the initiates of intervention but subject to the well-intentioned but paternalistic Western pen-pal program.

An I-Kiribati (a Kiribati national) child narrates the video and is presented as a tokenized portrayal of the nation’s identity in the face of a changing climate. The narrative suggests a primitive and ignorant Kiribati, yet this narrative is more representative of Western Poland’s view of Kiribati than that of an I-Kiribati child or of the nation’s self perception. From the narrative’s perspective, anything different than Western is presented as lesser in order to demonstrate the supremacy of developed nations. The Polish children’s letters and drawings symbolize the island nation’s communication with a northern world. The Kiribati child explains their isolation from the North, a place to which “nobody has ever been,” by pointing out differences of experience between children in Poland and the other Poland. Their isolation from the Western world’s “mature wisdom” is negatively implied. With I-Kiribati depicted as dependent on a paternal authority, it becomes the Polish children’s duty to explain the Kiribati’s situation to the I-Kiribati.

The video’s implied isolated history of Kiribati, absent of western influence, is not true. It ignores the Republic’s history as a British colony and the use of the Line Islands by the United States and United Kingdom for nuclear weapons testing in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Kiribati gained self-rule in 1971 and split from the Ellice Islands in 1975. The Gilbert Islands became independent and known as Kiribati on July 12, 1979. Ignoring this history trivializes developing countries’ concerns of autonomy and disregards the potential risks associated with a colonial relationship that may currently exist or could re-establish itself in the future.

Kiribati has not been inactive in international climate discourse. For example, in 2009, Kiribati became one of ten countries to sign the Bandos Island Declaration, thereby pledging to demonstrate moral leadership by cleaning up their economies as part of a commitment towards carbon neutrality. A year later, Kiribati hosted the Tarawa Climate Change Conference (TCCC) to provide a forum for vulnerable states and their partners. The conference sought to create an enabling environment for multi-party negotiations under the auspices of the UNFCCC. The ultimate objective of TCCC was to reduce the number and intensity of fault lines between parties to the COP process, explore elements of agreement between the parties and thereby to support Kiribati’s and other parties’ contribution to COP16 in Cancun.

In this video, the Kiribati child goes on to narrate differences of experience between the two Polands, as revealed to them via the pen-pal letters. The islander’s lack of experience with snow is contrasted by their familiarity with intensified sun and drought. The emphasis on climatic effects specific to Kiribati circulates the idea that climate change only warms and does not pose a threat to developed nations such as Poland. Climate change will affect the whole globe, although developing nations who are least responsible for contributing to climate change are expected to disproportionately experience the negative impacts of climate change.

As students from both Polands locate each other’s countries on globes, an I-Kiribati child describes environmental changes to islanders’ lifestyles–sick palm trees, decreased fishing yields, no longer having the privilege to waste food. To which the child helplessly admits, “But I don’t know why,” illustrating their dependency on parental figures to explain and take action against the cause of these changes. The implied ignorant and vulnerable situation of the Kiribati child to climate change characterizes the whole Kiribati nation as a child, dependent on a Western authority figure to enlighten the people and save its future. Authority is given to Western Poland and the developed country delegates in the audience at COP viewing the video.

The Kiribati child is asked to learn responsibilities in the face of change, where as the Polish children are not encouraged to take responsibility for their country’s climate emissions. Burden is placed upon those directly impacted to adapt to the changing climate. It is paternalistic to remind I-Kiribati that it is their responsibility to safeguard their culture, yet the narrator voices the parents’ (developed countries) desire for the children (I-Kiribati) to stop playing and “learn their [cultural] responsibilities.” The school children’s actual parents are not shown talking with their children about changes on the island. Instead they are presented dancing, singing and brushing the children’s hair. Besides emphasizing primitiveness and exoticism, this imagery is the extent of thought and action the video attributes to mature islander’s fight for climate justice. It does not acknowledge actions that islanders are currently taking to secure their rights in the face of imminent threats to their home, livelihood, culture, and history. The presentation characterizes Kiribati people–children and adults–as dependent and without agency in the face of changing environmental systems, thus victimizing the nation.

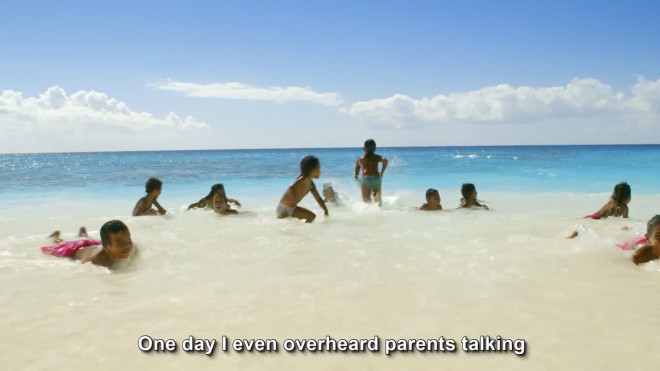

This video’s lens weighs I-Kiribati lifestyle against a Western ideal, diminishing the value of the former. This categorizes the loss faced by I-Kiribati as expendable or part of a sum-zero game. The narrator discusses rising sea level while children are shown playing on a beach. Through the child’s eyes, rising sea levels are presented as a threat to their play. From this viewpoint, the child’s relationship to the beach is one of whimsy, not of livelihood. Islanders daily lives are affected by rising tides, attributed to increase glacial melt, that threaten potable water on the islands especially in the capital city South Tarawa due to overcrowding and shallow location of fresh water reserves. Overlooking the impending possibility of a natural disaster, such as the Philippines’ Typhoon Haiyan, the evolution of these threats are projected to cause mass displacement to I-Kiribati within the next 30 years. Already, crops and homes are flooded annually. Despite waves encroaching on land and home, the lives of I-Kiribati are presented as expendable since what could be lost–their entire way of life–is depicted as child’s play. The Republic’s climate-related problems will not be “solved” once all 103,000 I-Kiribati are individually or collectively displaced. Consideration for less tangible or replaceable experiences, such as the I-Kiribati cultural connection to place complicates and gives perspective to climate change solutions.

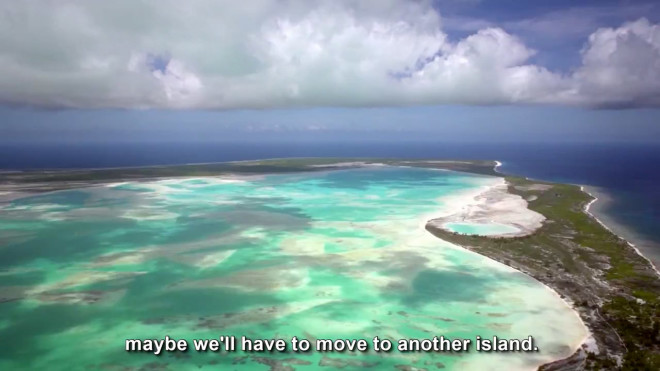

The impending possibility of moving to a different island is presented briefly as the narrator explains, “One day I even overheard my parents talking… maybe we’ll have to move to another island.” The prospect of forced migration is discussed as if it were just another conversation between developed powers to be overheard but not led or even contributed to by I-Kiribati. The passivity with which this perspective is mentioned normalizes exclusion of I-Kiribati from decision-making. Mentioned briefly as a side event of climate change, the severity of the situation is dismissed, and using the child’s lens to present this possibility assumes I-Kiribati lack the ability to conceptualize and make decisions regarding forced migration. The international delegates watching the video are given two perspectives with which to identify–the child’s and the parents’, where neither has responsibility for action or inclusion in decision-making. As implied by the child’s perspective, delegates are not encouraged to ask questions or take action because forced migration is not presented as a subject appropriate for the “young” viewer to voice concern about. The parents’ perspective is excluded from a model that should legitimately include those affected by policy decisions when the policy is written. Although the video depicts action and representation through paternal powers, the video allows paternal powers in the audience to easily evade responsibility by adopting the child’s perspective. The video neither mentions nor gives voice to the Kiribati delegates attending the conference, the appropriate representatives to consult with about Kiribati perspective. Instead, the video quickly moves on.

Contrary to the video’s representation of Kiribati’s lack of agency in climate crisis, I-Kiribati have been speaking out to the international community for several years. In 2008, Kiribati declared 150,000 square miles of the Phoenix Islands a fully protected marine park. Kiribati President Anote Tong explained that the creation of the UN World Heritage Site Park was intended as a gesture, to be “a significant contribution to the world community in the hope that they would also act.” Since then President Tong has increased the intensity of Kiribati’s adaptation strategies, evolving from “gestures” to full-scale, direct engagement of the international community in present day. President Tong has not been shy to stand up and confront the international community on their relationship to climate change and their current inaction declaring, “This is not caused by us. This is caused by you.” Kiribati’s Minister of the Environment Tiarite Kwong encouraged the delegates during the COP19 High Level Segment to ask harder questions beyond adaptation since Kiribati’s fate is an “early warning of what will happen further down the line for everyone.” The scale of the climate crisis demands collective action since, “we cannot answer these questions alone,” he noted.

In the final sequence of the video a Kiribati child is asked by their Polish pen-pals, “who do you want to be when you grow up?” The video fades out and the next speaker notes, “This could be any child asking that question… It is up to us here to help them with the answer.” This argues that it is up to the Warsaw negotiations to save the world’s children by defining their identity. Aside from delegates’ presumption of authority in assuming responsibility for human identity, stating that this could be any child from around the world overlooks the specific situation into which Kiribati children are born. Although the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change estimates that 200 million forced migrants will exist by 2050, I-Kiribati face a near future where they very likely will have to trail blaze a climate migrant life.

Already, many Kiribati do not have the privilege of choosing their vocation. Economic opportunity is limited on the islands. The romanticized dream of relocating for broader opportunities will likely not be a reality for many. Forced migration has the potential to dictate migrants’ jobs. Kiribati government is taking action to help ensure immigrant status for their citizens by training people to be skilled laborers in order to protect their citizens from a refugee status that has the potential to force them to live as second-class citizens. One program called the Kiribati Australia Nursing Initiative trains Kiribati youth to become nurses. The government is positioning its citizens to rely on marketable skills to pull themselves up from climate refugee to immigrant status, taking action to identify and alleviate the barriers their citizens might face as forced migrants and creating avenues for social mobility. Still, a lack of cooperation by foreign governments compounds the climate uncertainty, causing the government to spearhead initiatives that may prioritize other nation’s needs before safeguards protecting individual worker freedom and local culture, reinforcing Kiribati as developing/dependent.

Governments have not been open to recognizing the refugee status of climate migrants. In 2008, Kiribati first asked Australia and New Zealand to accept Kiribati citizens as permanent refugees. Recently, New Zealand’s High Court set a precedent by rejecting I-Kiribati Ioane Teitiota’s application for refugee status on the grounds that climate change did not directly persecute Teitota and his family. The judge dismissed the responsibility for the court to alter the scope of the UN Refugee Convention, insisting that countries have the option to alter their legislature to accept climate migrants if they choose. However, with the many migrants that currently exist and the millions expected, the possibility of countries willingly setting an alternative precedent seems slim.

Kiribati needs more than the help Western powers such as Poland or Australia are currently willing to give. Since 2010, President Tong has been working on strategies to facilitate the migration off of the islands and to do so in a progressive way. One strategy involves buying land from Fiji for the displaced Republic. However, President Tong notes, “What we need is the international community to come up with an urgent funding package to deal with that ambition, and the needs of countries like Kiribati.” Although funding structures have not engaged much with loss and damages in the past, much of the negotiations held at COP19 focused on potential strategies to fund for loss and damages felt by countries especially vulnerable to the effects of climate change. Since investors can benefit when local green industries are kick-started, mitigation efforts are often considered financially attractive to more developed countries (MDCs). Adaptation efforts, for example building a seawall, can directly benefit the developing country but not necessarily the MDC. In cases such as Kiribati, mitigation will not change the impending effects which will play out on too short of a timescale for even drastic mitigation efforts to reverse. This leaves Kiribati, a nation with limited resources and currently depending greatly on foreign aid, to struggle with the financial burden of climate change.

Developed countries are asked to step up to the plate by opening their doors to migrants and honoring their financial pledges. By associating these pleas with the video’s non-threatening child, the solicitation for developed countries to take responsibility for those portrayed as powerless is made to seem non-threatening. Cases like this video build support for the caretakers of threatened victims, encouraging countries to step up to be hailed as saviors. Still, the same portrayals also allow countries to back away from these commitments since the recipient is deemed powerless, unable to hold “higher powers” accountable.

Accountability is not portrayed as an attribute necessary for productive international climate negotiations. The video does not criticize Poland and other countries that have pulled pledges and limited their ambition. Countries’ pledged action, coupled with unreliable follow-through, results in an oppressive stalemate for developing countries currently facing serious threats resulting from climate change. Developed countries are allowed a photo shoot, handing over a large check that ultimately bounces. Western power unaccountability has plagued COP since the United States signed but did not ratify, and Canada withdrew completely, from the Kyoto Protocol, the legally binding emissions reductions declaration that initiated the meeting of the Conference of the Parties.

The savior-complex of the video hits home when the speaker states, “I care for Poland, but also for the other Poland as well”. The motto of the conference is “I Care”, prominently displayed on every sign promoting the conference. As a conference goal, the motto reinstitutes the binary between saviors and saved, developed and developing. It proclaims that sympathizing with other countries, as opposed to action and responsibility, is an avenue towards a successful conference, or even further, that countries can fulfill their responsibility to climate change by assuming responsibility for the care of developing countries that are incapable of caring for themselves. This paternalistic encouragement for verbalized ambition is striking and hypocritical when expressed concern is not translated into action. “I Care” is a motto of empty words without a component of required action.

Before the mayor introduced the video, Executive Secretary of the UNFCCC Christina Figueres heralded the Olympic motto, “Swifter, Higher, Stronger,” to the delegates. Contradicting the game rhetoric of this motto, the following speech states, “we must stay focused, exert maximum effort for the full time and produce a positive result because what happens in this stadium is not a game. There are not two sides, but the whole of humanity. There are no winners and losers, we all either win or lose in the future we make for ourselves.” Ideally, yes, COP would work towards a solution to climate change that prioritized all humans equally. We all face to lose a great deal. Yet sadly it is a reality that some will lose more, sooner and some will view this as opportunity for profit and advancement of power. Divisive strategies label the environment or an “other” as the opposing side, invigorating a sense of competition between powers to encourage a struggle for dominance. This nationalism expresses itself through the negotiation’s savior/saved dynamic. The ability to claim “good global citizen” later down the line is used as a strategy by big powers in order to protect their self-interest. A race to the solution creates teams who weigh their resources, politics, expendable energy, citizens etc. against each other. The race’s goal becomes saving the earth for the advancement of your country–not for humanity.

Poland as the host country set a stage for oppression instead of justice, lacking consciousness of their influence. This introduction to the largest international climate negotiation normalizes paternalism as an appropriate response to calls for action by nations facing impending land loss, forced migration, and other severe consequences of climate change. Maybe Poland doesn’t really think about climate change negotiations as a game to win or lose. Still, the idea that it is their job as host to rally our emotions and tug at our heartstrings, presenting a group of people as victims, trivializes climate change negotiations, turning it into an institution not about justice but about having an emotional experience that validates privilege. Along these lines, Poland hosts the conference in hopes of being a savior country, and therefore worthy of higher status.

Sadly, there were countless examples that normalized colonial attitudes as valuable drivers of progress at COP19. Poland was certainly not the only paternalistic power, and the world stage is not the only place where this rhetoric and savior-complex are used to validate the environmental movement. Up to the point in time when these oppression-perpetuating events are taken seriously from international to local levels, COP will be representative of a system perpetuating environmental injustice. Until then, environmental justices will exist despite COP limitations. This will not change without opposition. More so, understanding the imperfection of international climate politics validates personal agency and responsibility in the climate movement.

The scale of climate change is of course huge and warrants international climate negotiations, but are we doing more bad than good if we don’t simultaneously address the injustice perpetuated by the claims of saving? Oppressive works, infused with a developed savior-complex as illustrated by this video, are representative of the current state of international climate negotiations. The current narrative is oppressive, yet the conversation on climate change is ongoing, and can be continually pressured to integrate and critique dialogues of justice and inclusiveness. Like climate change, oppression demands more than a nod of the head, rather it demands an everyday commitment. In this regard, current world powers have fallen short by playing a “game”. The future of climate negotiations does not have to follow these rules. Instead, it can break from them.

(Additional historical research on Kiribati provided by Caitlin McCoy & Brendan McIntyre.)