The Rise of the Third World

I recall quite vividly my view of the world when I was in elementary school. It all centered on the fact that I was an American, a native-born citizen of the strongest, freest, and most just country in the entire world. Even better, I had the good fortune to have been born in the era following what virtually every politician and pundit referred to as “the end of history.” The story went something like this: now that the United States has overcome the last bastion of evil in the world, the Soviet Union, the good times are going to roll forever. Our economy was booming year after year. Our country was admired and beloved by the entire world, and all I needed to worry about for the future was which one of the nearly infinite job offers I was going to accept. It’s so hard to choose when they’re all on equally attractive silver platters.

I recall quite vividly my view of the world when I was in elementary school. It all centered on the fact that I was an American, a native-born citizen of the strongest, freest, and most just country in the entire world. Even better, I had the good fortune to have been born in the era following what virtually every politician and pundit referred to as “the end of history.” The story went something like this: now that the United States has overcome the last bastion of evil in the world, the Soviet Union, the good times are going to roll forever. Our economy was booming year after year. Our country was admired and beloved by the entire world, and all I needed to worry about for the future was which one of the nearly infinite job offers I was going to accept. It’s so hard to choose when they’re all on equally attractive silver platters.

Fast-forward to 2009, and the world appears upside down. Our booming economy finally went kaboom, and jobs are nowhere in sight. Far from being beloved and admired by the world, the United States is the target of widespread animosity. Some of our closest allies, Great Britain and Japan included, are consistently furious with us, and not only do we have a large number of strategic competitors, like Russia and China, we have a sizable number of outright enemies, like North Korea and Iran. What the hell happened?

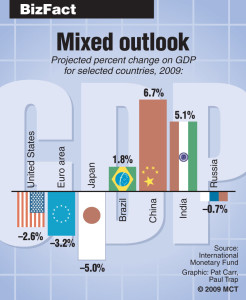

While our economy is in the toilet, elsewhere in the world growth is chugging along as though the crash of 2008 never happened. Countries like China, India, Indonesia and Brazil are all posting annual GDP growth rates above 5% despite the global recession. In China both state and private enterprises are going on a spending spree, buying out the assets of foreign firms at rock-bottom prices. The situation appears even starker when you look at foreign stock markets: the Brazilian stock exchange, for instance, is up nearly 70% from this time a year ago, while China’s Shanghai Index is up 90%. Essentially, those lucky few who do have money to invest are not confident enough to do so in the United States. In aggregate, that basic fact explains the falling price of the U.S. dollar.

However, just because other parts of the world are doing quite well doesn’t actually mean the world is upside down. A good number of the challenges the United States faces are merely the current chapter of ongoing trends. North Korea is the same old thorn in our side it’s always been, albeit now with nuclear weapons, and China’s current economic domination is hardly a surprise given the rate at which it has been growing for the past three decades. The Chinese economy hasn’t grown at less than 5% a year since 1990, while the United States hasn’t seen 5% growth since 1984.

Still, China’s economy is only about a third the size of the United States’ at market exchange rates. The real story, therefore, is that countries like Brazil, India and China (often referred to as the BIC economies) are hitting their stride right at the point the United States is at the weakest it has been since the Great Depression. To put it another way, it’s not that these countries are suddenly stronger than the United States, it’s just that they are a lot stronger than they used to be, and the United States has gotten used to having no meaningful competition.

While U.S. resources are at work in two foreign wars and mopping up its economic mess, these countries are basically the only big players with money to burn. That doesn’t mean they’re suddenly stronger than the United States, but it does mean that they are much more flexible in choosing where to apply their power.

While U.S. resources are at work in two foreign wars and mopping up its economic mess, these countries are basically the only big players with money to burn. That doesn’t mean they’re suddenly stronger than the United States, but it does mean that they are much more flexible in choosing where to apply their power.

The result is that while the governments and firms of the Western world are drowning in debt and desperate to sell off their assets, developing firms, awash with trillions of dollars worth of foreign currency reserves, are swooping in and able to buy up far more than they could in a normal economic climate. As a result, there are signs of developing world power everywhere, such as China’s recent $9.2 billion investment in Venezuela’s oil industry.

No U.S. firm is making investments of that size these days. The only time anyone talks in billions in the United States is when they’re asking the government for money, such as when General Motor’s financial arm just requested their third bailout from the U.S. Treasury, this time for $5.6 billion.

The United States finally posted GDP growth numbers at the end of October, but those numbers are driven almost entirely by government spending. Programs like “Cash for Clunkers,” which subsidized purchase of new cars to the tune of $3 billion, are a nice shot in the arm for the industries they help, but everyone is aware that such massive expenditures cannot continue forever. At some point, the U.S. economy has to find a way to return to sustainable growth and at the same time pay down all the massive debt it has accumulated while trying to stave off adepression.

Those two goals are at odds with each other. The key to paying down the debt is cutting government spending and raising taxes, but if the government moves too quickly on either of those things, it could choke off the measly beginnings of growth we’ve only just begun to see and worsen our position even more. The government is thus walking a dangerous tightrope between two awful possibilities: unsustainable debt on the one side and a return to recession on the other. Perhaps worst of all, it must make this terrifying choice in a foreign policy climate that is radically different than the one it faced only five years ago. Then, the developing world was content to rise quietly, but now those countries want decision-making clout that is appropriate given their economic might.

It’s a much scarier world out there than the one I grew up expecting, but that should never be used as an excuse for refusing to make hard choices. America must be conscious and respectful of the fact that it cannot possibly endure the ongoing economic crisis without the cooperation and assistance of rising powers like China, to which it owes more than $800 billion dollars. Similarly, China and other rising powers should recognize that the current restraints on the United States will not last forever and that it is being judged for the quality of the international leadership it showed during the crisis period. Let’s hope they all choose wisely.

(Greg Allen, WUPR’s editor in chief, is a senior majoring in PoliticalScience. His email is gcallen@wustl.edu.)