Women Leaders: Are they here to stay?

In 2005, Ellen Johnson- Sirleaf was elected the President of Liberia after 14 years of civil war, becoming the first female modern African head of state. It is tempting to conclude that the rise of women such as Sirleaf signifies a positive trend in terms of the empowerment of females. The people of Liberia trusted a female leader to guide them out of a devastating civil war, an important a role as any.

The question remains whether the recent trend of female heads of state actually reflects an increasing gender equality, or whether it is spurred by citizens that seek a change which simply happens to come in the form of a woman. One might argue that electing a woman in reaction to the failure of an previous male is comparable to the commonly seen backlash against electoral incumbents–the people dislike a liberal president, so they vote for a conservative candidate.

However, women deserve to be elected because of their merits and qualifications, not because a member of the other gender has disappointed the citizenry. Marta Lagos, the executive director of the Chilean polling firm Latin Barometer claimed that “[South American female leaders] are not well-known as great leaders, and unfortunately, they are not rising to power due to their own merit but because they break with the traditional scheme of political leaders”.

Her theory suggests that women oftentimes do not come to positions of leadership because they are more respected or empowered than in the past, but merely because the voters feel the alternative (men) has failed them. Moreover, this shows that female candidates are elected primarily because they are women and not because of their policies and qualifications, regardless of gender. In addition, if a female leader is unpopular, she may bar the door to further females from being elected due to unfair associations between two otherwise unrelated female candidates.

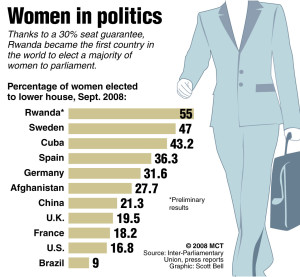

Historically and recently, women have often come to power thanks to quotas that require a certain percentage of the legislature be female. Though this helps bring women into government, a change in the attitude of the citizens towards female officials cannot be enforced top-down. Forbes magazine has stated that in some countries, such as Afghanistan, women fill one third of the seats but are “clearly excluded from the decision making process;” women do not have an active role in government, although on paper it might appear otherwise.

In addition, though many European countries such as Belgium, Germany, and France have quotas, “just 10% of European women believe that mandatory quotas are the way to increase the proportion of women in parliament” (Forbes). This reveals the ambivalence female voters have towards such quotas which seem to openly acknowledge the inequality between the sexes in government and attempt to rectify it with force. These quotas imply that women are not popular, qualified, or respected enough to win an election on their own.

On the other hand, women in more progressive countries may assume an equality that women in other countries may not have the luxury of. French women may believe that they do not need quotas to ensure their voice in government, but for less socially liberal countries which have enacted successful quota systems such as Rwanda, giving women a place in government allows an opportunity for equality that may not have existed otherwise.

Nicholas Kristof postulates that one of the major issues for women in government is “public prejudices”. A woman who wears a suit, debates men openly, and demands public attention, that is, is an effective government official, goes against many traditional ideals of womanhood–reticence, purity and modesty. Though these gender roles and standards may have been forced under the surface in some societies, they still leave a powerful impression in the collective memory.

Physical appearance is also a double-edged sword for women. Obviously, if a woman is attractive, she is more likely to resound with male voters. This can unfortunately become an implied accusation against her intellect, as is the case with Sarah Palin. Furthermore, powerful women are often praised but slyly damned for their apparent authoritativeness (Read: masculinity): Margaret Thatcher and Golda Meyer were often said to have “the biggest balls in their cabinets”.

In what is called the “Goldberg Paradigm,” Phillip Goldberg conducted an experiment in 1968 which revealed a single essay was an average scored higher by participants who were told the author was male. This experiment, demonstrating a kind of implicit, subtle discrimination, reveals the very real challenges female leaders face in modern society.

The only way to effectively empower the “other” half of humanity and to truly give them their deserved voice in government is through social change. Change de jure cannot accomplish the same effect as a change in the citizens’ attitude. Social change is arduous, sluggish, and cannot be forced. Supporters can aid it, but top-down measures imposed on an unsupportive populace, such as quotas, will not create lasting change. Only by overcoming the entrenched prejudices women face, such as expectations of femininity and modesty, can a truly empowered woman leader emerge. Only as society changes its perceptions of the role of women will people see female leaders as equally deserving of governmental power.