When One Nation Becomes Two

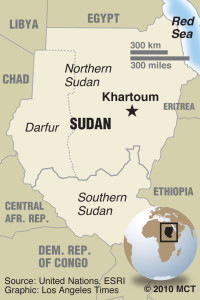

On January 9th, citizens living in southern Sudan will vote on a referendum to secede from the northern part of the country. A clock in the town of Juba, the political center of southern Sudan, counts down to this referendum, symbolical of the locals’ excitement to part from the hegemonic north. Nearby, the Darfur genocide crisis that continues to plague the area is not an isolated event. It’s all related, part of two brutal civil wars that have been for decades tearing the nation apart; as of late, literally.

Sudan has traditionally been seen by many as the bridge between the Arab and the African worlds—one not particularly easy to cross. The north and the south of Sudan are just about as culturally and religiously different from each other as you could possibly imagine. In the north, Arab culture dominates, and the majority religion is Islam. In the south, the predominant culture is more traditionally sub-Saharan African, and the primary religions are animist belief systems and Christianity. Ever since the country gained independence from Britain in 1956, the cultural and religious systems of the north have been heavily imposed on the whole of Sudan, resulting in southern resistance and the ongoing strife.

In particular, this imposition of a differing set of beliefs can in large part be attributed to the current Sudanese president, Omar al-Bashir. Al-Bashir arose to power in 1989 through a bloodless coup, and this past April, won the first ostensibly democratic election the nation has held in 24 years. I hesitate to call the election democratic because many believe that al-Bashir, who is notorious for his corruption, rigged it in his favor. While there is no proof, it is generally not unsafe to consider that leaders who are in power through a coup have significant sway in any following elections. Whether he is rightfully in power or not, al-Bashir has imposed northern ideals throughout the whole nation, a primary cause of the Sudanese civil wars. Many attribute the Darfur genocide, just a single episode of the extensive bloodshed since Sudan’s independence, to al-Bashir. Because of these accusations, he is currently on trial for war crimes, the only current head of state in such a predicament. To drive home his impositional tendencies further, al-Bashir has said that if the south secedes, he will impose Shari’a in the north, in an effort to make northern Sudan officially an Islamic state.

My first response to this situation was wondering: How did two peoples so immensely different from one another end up together in the first place? This is not the same as the American Civil War, where regional differences led to ideological differences, which in turn led to secession. In the Sudanese case, ideological and cultural differences existed long before the country gained independence. Thus, one should look to colonialism as the primary cause of Sudan’s problems. It seems to me that Sudan’s independence process was dangerously arbitrary; occurring at the time of mass European decolonization in Africa. It’s as if Britain backed out of the region and drew a national border at random. And now, after over half a century, the people want that to change.

Despite the referendum on schedule for next month, the potential new border still has not been set. Money, of course, is a factor. Sudan is one of the most oil-rich nations of Africa, but most of the country’s oil is found in the south. On the one hand, the north might not want to draw a new boundary where the south gets all of the resource wealth, a potential cause for even more strife. On the other hand, some see oil as a potential area that could keep the two sides friendly if they do end up splitting. Mutual desire for the oil wealth may bring the two sides together diplomatically if the split ends up happening peacefully.

As you can see, this situation is extremely complex, far more so than the south simply saying “we want to secede” and secession then happening. To better understand the context, one needs to consider the past, but one should also consider the future: what will happen if the current nation of Sudan does in fact split? I am wondering particularly about those who have their roots in the south but live in the north. Since the referendum was announced, many of these people have moved back to the south, but a fair number still remain in the north. What will happen to these primarily non-Muslim people (and Muslims alike) if the north does in fact impose Shari’a on al-Bashir’s whim? Al-Bashir will go from an imposer of northern Arab and Islamic values to being completely intolerant of this significant minority in his newly allotted half of Sudan, and the results would be tragic.

What message would a Sudanese split portray to the rest of Africa, the rest of the world? The African Union fears that a Sudanese split would incite other secessionists around the continent. Other nations undergoing similar domestic, regional conflicts of interest may feel not only that they have a right to secede, but may even feel encouraged to do so. Is this kind of outright division the right answer to such a complicated historical struggle?

Is there even a right answer? Experts seem to agree that the nation will inevitably split. Whether this bifurcation happens via a timely, democratic, and peaceful referendum or through continuing bloodshed is a matter that only time will tell. I will certainly be following this issue in the coming weeks, and I wrote this article before the scheduled referendum in the hope to spark more interest on the issue. I urge you to follow it in the news; the results affect a much wider area than simply Sudan.

Stay tuned for my next column, where I will compare and contrast two leaders in South America on opposite sides of the political spectrum and compare their respective political systems to that of the United States.