The Great Truth of 1726–A Review Essay

“What neither is, nor was, nor e’er shall be?” — Elphinston

“The usefulness of an opinion is itself matter of opinion.” — John Stuart Mill

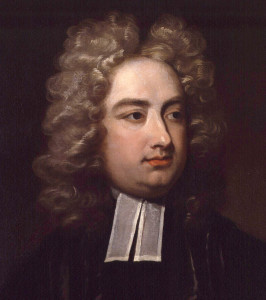

The solemn Irish thinker, Mr. Jonathan Swift, was indeed a remarkable man. In his thoughtful and elegant book, Gulliver’s Travels, Dean Swift presented us with what remains a very powerful philosophy. Briefly, in his encounter with the rational Houyhnhnms, Gulliver discovers a great truth: man is absolutely incompetent. And what is worse, all of his attempts at improvement are just indications of his vice. Universities and the estbalishment of laws and government; the institutions of property and commerce; literature and the arts; and social codes of conduct; all of these things exist only because we are unable to follow the dictates of reason. The Houyhnhnms, perfectly rational, had none of these things.

Gulliver, to be sure, resists this truth at first. Indeed, it is a decidedly uncomfortable truth. But, when it is thought about intelligently, the logic of it seems irrefutable. Take, for example, the subsequent development of this philosophy by the great Anarchist thinker, Mr. William Godwin. His treatise, Political Justice, posits that government becomes increasingly superfluous in proportion to the proper exercise of reason. Thus, when men become rational, government will no longer be necessary. His was the creation of Rational Anarchy. I should also note that this thesis, propounded during the Enlightenment, was received with considerable applause. Its relative obscurity today is, I think, more an accident of history than anything else.

This truth was also re-stated somewhat in the political works of another great thinker, this time the Austrian economist and philosopher, F. A. Hayek. Hayek wrote that there would simply be no room for a system of law in “a society of omniscient persons,” for like all social institutions, law is just another “adaptation to our ignorance.”

These ideas all represent, in one way or another, that great truth of 1726, “That, our Institutions of Government and Law were plainly owing to our gross Defects in Reason, and by consequence, in virtue; because Reason alone is sufficient to govern a Rational Creature; which was therefore a Character we had no Pretence to challenge.” Note in particular the final clause, which stands for the idea that all attempts at intelligent planning are futile. Government and law, we must remember, are just examples of man’s pretense to Reason.

Now, taking all of this to be true, you might ask now, What are we to do? I am a pragmatic man. Theory is good up to a point, at which time it becomes necessary to begin thinking about reality. The dissolution of government is obviously not an option. Godwin himself, the father of anarchy, believed that this was possible only gradually. However, like Hayek and Swift before him, I am not predisposed to optimism. Godwin seems to me to paint too pretty a picture. By all accounts, man quite plainly is still shooting in the dark. Our system of government and law has become more complex than it was in the Enlightenment. Godwin was mistaken, since according to him the exact opposite should have happened.

But if gradual anarchy is not the answer, then what? I believe that the answer is in a system of rules, specific and exhaustive. These rules would not be compromised, expanded, or re-formulated — which is to say, we would no longer give any credence to the silly images produced by our false reason. Again, remember the great truth of 1726, that “Controversies, Wranglings, Disputes, and Positiveness in false or dubious Propositions, are Evils unknown among the Houyhnhnms,” and that “Knowledge, if it were certain, could be of no Use.” I propose that we try as best we can to emulate the Houyhnhnms. Our system, of course, will be flawed and riddled with terrible inconsistencies, but it would have the singular advantage of being a sort of constant and predictable chaos. Effectively, it would be a roadblock on man’s pretense to reason. Try, if you can, to look at it from the Houyhnhnms’ perspective: they “looked upon us as a Sort of Animals to whose share, by what Accident [they] could not conjecture, some small Pittance of Reason had fallen, whereof we made no other Use than by its Assistance to aggravate our natural Corruptions.”

This proposal, I should also say, is not impracticable. We see it somewhat already in the law. Look to the rules of Evidence, the rules of Civil Procedure, and the UCC codes. Formal codification is indeed a manageable enterprise. The challenge, of course, will be in thwarting attempts at accomodation. I will be the first to admit that rules, when rigidly applied, can at times seem rather severe. Our attitudes change and novel circumstances invariably appear. But remember, again, the great truth of 1726, that “Nature and Reason were sufficient Guides for a reasonable Animal, as we pretended to be, in shewing us what we ought to do, and what to avoid.” I propose, therefore, that we definitively settle on a course of conduct, preferably embodied in a system of rules, and then stick as closely as we can to it thereafter. It is a flawed approach, to be sure, but given the great truth of 1726, I can see no better alternative. This approach would keep resulting harm to a minimum; the inevitable confusion resulting from our institutions of government and law would be made predictable; the system would be free of those complications occasioned by the introduction of new ideas and proposals for change; and, perhaps most importantly, our small “tincture of Reason” would no longer be responsible for making man “that vain animal who is so proud of being rational.” — John Wilmot, A Satyr Against Reason and Mankind.

SOURCES

Jonathan Swift, Gulliver’s Travels, Oxford Classics 2005.

William Godwin, Enquiry Concerning Political Justice, Bibliolife 2009.

F. A. Hayek, Law, Legislation and Liberty, Volume 2, Chicago 1978.