From Mandela to Malema

Nelson Mandela spends little time in the public eye these days. Now in his nineties, his health has declined considerably, leaving a vacuum for an elder statesman to guide South Africa seventeen years after apartheid. The South Africa molded in Mandela’s image has made remarkable strides since he first became president, becoming the most politically and economically powerful nation in Africa. It has the world’s 24th-largest GDP, making it a beacon of hope in a region of lackluster development and dire poverty. Yet all of that could come crashing down, thanks to the violent rise of provocateur Julius Malema, seeking to capitalize on the darker side of South Africa’s ascent.

Beyond the gilded skyscrapers of Johannesburg, a menacing slew of threats hangs over the country’s still nascent development. Well over half of black males under the age of 25 are unemployed. The nation as a whole ranks 129th on the UN’s human development index, placing behind several of its less economically advanced African neighbors. And, after seventeen years in power, the ruling African National Congress (ANC) has had its fair share of politically damaging corruption scandals.

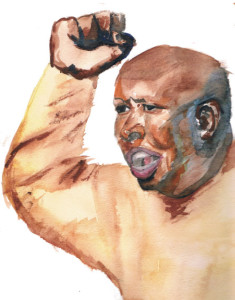

Enter Malema. Malema leads the ANC’s Youth League, which he has effectively utilized as a bully pulpit to galvanize support from youths disenchanted with an out-of-touch ruling class. Malema has tasted blood among the ruling elites, helping current president Jacob Zuma bring down former president Thabo Mbeki in an electoral coup in 2006. Now it seems Zuma may be next. If the marginalized masses continue to miss out on South Africa’s economic rise, they may be more willing to listen to the populist Malema, who tells them what they want to hear.

Malema’s gospel is similar to that of other African dictators; indeed, he counts Robert Mugabe and Muammar Quaddafi as personal heroes. Malema advocates the nationalization of private (and currently quite profitable) mining companies. South Africa has some of the world’s richest mineral reserves, composing 90% of the world’s known platinum reserves, 80% of its manganese, 70% of its chrome, and 40% of its gold. Doing so, however, would put South Africa at risk of becoming like its neighbor to the north, Zimbabwe, where Mugabe’s revolutionary Zanu-PF ruling party has nationalized the country’s mining and agriculture industries with calamitous results. In the words of former Zimbabwean opposition leader and current Prime Minister Morgan Tsvangirai, Zimbabwe went from “breadbasket to basket case.” Nationalization in South Africa, though a popular cause among the poor, could completely derail its economic miracle.

Malema also threatens to ignite the always-simmering racial tensions of a nation whose scars of apartheid are still at the forefront of the national discourse. Seventy-nine percent of South Africans are black, with 9% white, 9% mixed-race, and 3% Asian. White citizens tend to have a larger share of the country’s wealth relative to the size of their population, making them a target of populist anger. Helen Zille, the white leader of the opposition Democratic Alliance party, has called Malema a “dictator-in-waiting.” Malema recently was found guilty of hate speech when he encouraged the singing of “Shoot the Boer,” an apartheid-era black nationalist song that advocates violent resistance against the ruling whites. Many saw the court ruling as a message to Malema from the elders of the ANC, specifically from Zuma. But after his experience as a kingmaker, Malema is increasingly unwilling to follow the lead of his superiors. With so much attention, domestic and international, directed towards him, he seems uninterested in the slow path to power and stature commonly observed within the ANC.

Like his revolutionary heroes, Malema is unwilling to sit on the sidelines for long. He makes fiery speeches about the lack of leadership and the disease of corruption in South Africa, stopping just short of mentioning President Zuma by name. Zuma has taken notice, and many in the ANC favor censuring Malema or even expelling him altogether. This is unlikely, however, due to Malema’s popularity with large segments of the population, particularly the 43% of South Africans living on less than $2 a day.

Zuma and Malema appear to be on a collision course heading into the ANC’s party conference in 2012. Malema may believe his time has come and seek to become the party’s leader. This gamble could lead to a dangerous battle between South African populists and the pro-business ANC, possibly leading to an ugly and economically damaging protracted political struggle. This could deal a major blow to foreign direct investment in South Africa and challenge its status as the model democratic African nation. Beyond simply discrediting Malema as a dangerous, destabilizing force, Zuma must revamp development programs such as the underperforming “Black Economic Empowerment” that tackle the ANC’s addiction to corruption and that bring employment prospects to South Africa’s disgruntled unemployed. There is only one thing that would be more damaging to South Africa’s future than a bitter political stalemate, and that would be a Malema presidency.