Carrots and Sticks

A stable, cooperative Pakistan is both a prerequisite for eradicating al-Qaeda and a key for NATO success in Afghanistan. As Michael Mullen has emphasized, “there is no solution in the region without Pakistan, and no stable future in the region without a partnership.”

Historically, however, US policy toward Pakistan has consisted of flooding the country with both military and developmental aid and hoping that the country goes along with our proposals. The problem, as the RAND corporation noted, is that, “U.S. strategy has focused too much on carrots (positive incentives) and too little on sticks (negative incentives).” .

Despite this, Pakistani-US relations are in a state of decline. While the United States is for the first time in a long time bringing out some “sticks”—namely accusations by top military and government officials that Pakistan is aiding terrorists—these are flimsy twigs that serve only to humiliate and anger Pakistan. Consequently, Pakistan is considering barring the flow of NATO materials to Afghanistan through its borders, which that accounts for 70% of the supplies in Afghanistan.

Clearly, American policy towards Pakistan must be revised. To do so, we need to find the appropriate negotiating tools and focus them on realistic goals.

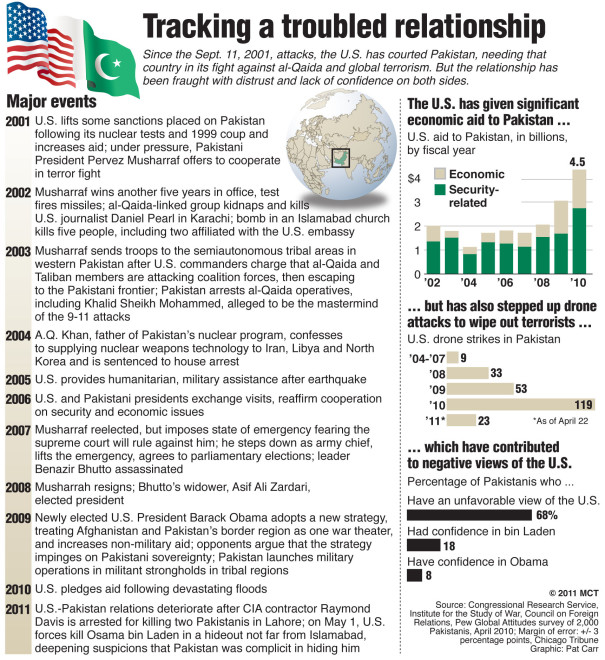

The largest carrot in the US hand is neither money nor weapons,but in fact the termination of unmanned aerial vehicle (“UAV” or “drone”) attacks. These strikes are immensely unpopular among the Pakistani people, as between 30 and 98% of those killed by the airstrikes, depending on one’s definition of militant,* are civilians. Its important to emphasize that drone strikes are despised not only by those directly affected and terrorized by the attacks, but also by those in urban environments who view the strikes as a humiliating violation of Pakistani sovereignty.

Without even taking into account the benefits that could flow from the termination of Drone attack’s use as a negotiating device, stopping these strikes would ultimately help the United States. We would lose the lives of a few, replaceable militants, and gain a more stable, less anti-US Pakistan, a Pakistan that would export less terror, produce fewer recruits for the Taliban and al-Qaeda, and function as a slightly safer home for nuclear weapons.

In order to reap the diplomatic benefits however, the US must exchange drones for increased military cooperation on the Afghanistan–Pakistan border. While military cooperation is unpopular with Pakistanis, drone attacks are considered a greater threat, making a trade mutually beneficial. Furthermore, unofficial military cooperation has some precedent making its increased use not only plausible, but probable with the termination of US drone strikes.

As for sticks in the relationship, there is a clear one at our disposal: US aid to Pakistan. This aid totaled about $37 million in 2000, has skyrocketed since September 11. In 2010, it consisted of about $4.5 billion, of which about 70% was military—the rest is primarily developmental.

While reducing military aid to Pakistan has the potential to be a tremendously effective negotiating tool, Congress’s recent initiative to make aid conditional on proof that Pakistan is actively hunting down terrorist organizations is misguided. First of all it fails to differentiate between developmental and military aid. Cutting developmental aid often forces citizens in need to turn towards insurgent movements. Secondly it is premised on the rather naïve notion that the Pakistani government has the power to prevent factions such as the ISI from pursuing terrorist activities. Instead, Pakistani military aid should be conditional on the adoption by the Pakistani military of Counter Insurgency or COIN military strategies.

Over the past few years, the Pakistani military has been engaged in an all out war with the Pakistani Taliban and other insurgent movements in the north. While the military claims to be making gains in this conflict, insurgent groups have already returned to just about every area previously “cleared” by the Pakistani military.

This is because the Pakistani military is primarily focused on a war with India and thus with conventional warfare. While COIN strategies are demonstrably more effective, they require thorough training and a particular mindset. This training would likely be carried out by US or NATO Special Forces officers. While this arrangement has precedent,a large scale training of the Pakistani army would be embarrassing for Pakistan This is precisely why they have avoided adopting COIN in the past. Nonetheless it must be pushed for—either with carrots, sticks, or a combination of both.

Imperfect as the current Pakistani government may be they must win this war, and COIN is the only way to do it. A secure Pakistan can begin to seal the porous border between Pakistan and Afghanistan, something Pakistan has an interest in doing as most of its current instability originated in Afghanistan. A stable Pakistan means safer nuclear weapons and reduced terrorism. Ultimately a truly strengthened Pakistani government may, in time, be able to challenge the ISI.