Pyongyang 2012: Policy Shift or Brinksmanship?

Without its nuclear deterrent, the North Korean regime’s continued existence would be unlikely. Its people are starving, and even its military, which is granted most of North Korea’s meager resources and is the 4th largest in the world, is beset by fuel and ammunition shortages and uses antiquated equipment. Threats of US-South Korean invasion would likely prompt an arranged capitulation, and either regime change or unification.

Without its nuclear deterrent, the North Korean regime’s continued existence would be unlikely. Its people are starving, and even its military, which is granted most of North Korea’s meager resources and is the 4th largest in the world, is beset by fuel and ammunition shortages and uses antiquated equipment. Threats of US-South Korean invasion would likely prompt an arranged capitulation, and either regime change or unification.

To put the military disparity between North and South Korea in perspective, consider that North Korea’s Gross National Income, roughly $25 billion, is smaller than South Korea’s 2009 military budget of $27 billion. Any decision to disarm implies an acceptance of unification on South Korean terms in the near future.

Some argue that China would guarantee North Korean independence due to its desire for a buffer state between China and the thousands of US troops in South Korea. There are, however, a number of reasons to doubt the strength of China’s commitment to North Korea.

North Korean-Chinese relations have recently deteriorated. In 2006 and 2009 China agreed to enforce economic sanctions on North Korea, marking a significant shift from former publically unqualified support for the authoritarian regime.

Furthermore, the creation of a prosperous North Korea via its integration with South Korea would benefit China in a few ways. First, it would create a profitable trading partner—South Korea is China’s 4th largest trading partner and the Chinese conduct roughly 100 times more trade with South Korea than with North Korea. Secondly, China’s aid to North Korea is a costly commitment – China provides 80 percent of North Korea’s consumer goods and 45 percent of its food. This is motivated by a desire to prevent the regime’s total collapse and the subsequent flood of unwelcome refugees.

Lastly, it is important to emphasize that China values regional stability above all else—this explains why it has recently begun chastising North Korea for its belligerent actions, which threaten to spark regional conflict. Although an independent North Korea made a lot of sense to the Chinese during the Cold War, its current risks and costs are beginning to outweigh its benefits.

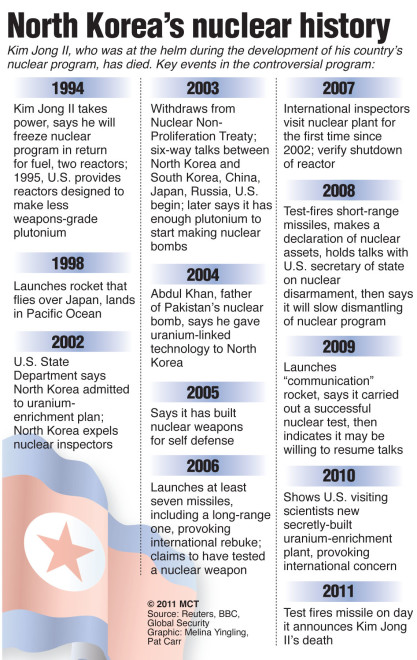

As Chinese support for North Korea wanes, the North Korean commitment to its nuclear program is likely to get even stronger—in fact, North Korea began its quest to attain a nuclear weapon as a result of its vulnerability after the fall of the USSR.

Unlike Iran, whose nuclear ambitions are part of its attempt to take on the role of regional hegemon in the Middle East, North Korea does not use its nuclear weapons to project power, instead it thinks of its nuclear program as a bargaining chip and deterrent.

North Korea consistently attempts to demonstrate that it must be considered a threat to South Korea and the United States through unprovoked attacks on ships and islands. Although these attacks are significant and have, over the past few years resulted in roughly 100 deaths, North Korea calculates the attacks such that they are not sufficiently threatening as to force the US and South Korea to risk a nuclear attack by retaliating militarily.

This policy is called brinksmanship; the North Korean government basically uses the threat of violence (protected by the nuclear deterrent) and the incentive of deactivating its nuclear program to secure aid.

North Korea’s nuclear program functions as a bargaining chip. As a 2010 Congressional Research Service report notes, “Pyongyang’s willingness to negotiate has often appeared to be driven by its internal conditions: food shortages or economic desperation can push North Korea to re-engage in talks, usually to extract more aid”.

North Korea has strategic interests in pursuing policy on the brink of what will result in an American and South Korean escalation. It alternatively advances and retreats from this cliff edge and secures aid in its retreat.

The question we must now ask ourselves is whether North Korea’s recent agreement to trade a moratorium on nuclear tests and uranium enrichment for food aid is a continuation of the policy of brinksmanship or represents a sincere shift in North Korean-US relations. There is some evidence for both points of view.

It certainly looks a lot like brinksmanship. The deal bears an eerie resemblance to an agreement between the United States and North Korea in 2008 which traded a moratorium on plutonium production for food aid. Unfortunately North Korea backtracked after receiving the aid and commenced inflammatory policies once more in April 2009 by resuming production.

That said, the recent succession of Kim Jong-Un after his father’s death may result in a more cooperative North Korea as explored in “Still Il”. The writer Max Cohen notes that the European educated Kim Jong-Un likely gained an appreciation for democracy as he witnessed the wealth and high standards of living it produced.

Unfortunately, Kim Jong-Un has been as prone to bellicose rhetoric as his father: he has publicly threatened an attack on South Korea in response to upcoming US and South Korean war drills. This may mean little as the gap between rhetoric and policy can be extremely wide in a country where extremist rhetoric is par for the course and policy is predicated on finding the balance between too much and too little force.

On the other hand it is often ignored that commitment to North Korea’s autocratic regime does not necessarily require a hatred of democracy. Instead, committing to North Korea’s independence (and thus nuclear program) could simply be the result of Kim Jong-Un’s practical calculation of his interests. Leading North Korea is extremely profitable. North Korea is described by US officials as the “Soprano state”. The country makes money off of state-sponsored crime: counterfeiting money, the drug trade, human trafficking and even insurance fraud.

Even if Kim Jong-Un does hope to steer his country towards reconciliation, it is unclear whether Jong-Un actually wields significant power or if he is currently functioning as a figurehead for a military council. Furthermore, the current proposed deal was actually initiated under the rule of Kim Jong-Il, which indicates that they may simply be a continuation of the policy of brinksmanship.

Even as a wave of democratization overturns authoritarian regimes in the Middle East and elsewhere, North Korea, the world’s only truly totalitarian state, likely intends to preserve itself as it has for decades: a foreign policy of violence, threats, and broken promises.