Attempts at Independence

BY BEN GOTTESDIENER

Between 1973 and the present, there have been numerous shocks to the energy marketplace, the oil market in particular. With each shock came a subsequent call for energy independence, and a national energy strategy to make the United States achieve it. However, with each call for independence and with each plan to achieve it, came an ultimate failure, as today the United States remains energy dependent. This analysis will look back on the marginal successes and major failures of national energy policies proposed by the last eight Presidents.

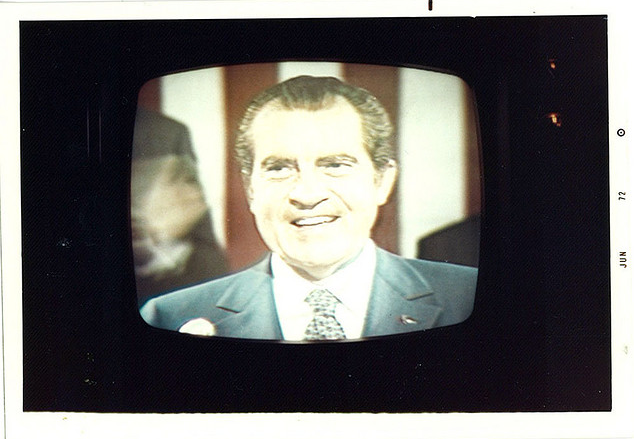

On October 6, 1973, Syria and Egypt launched a surprise attack on Israel. The United States responded by backing Israel financially and by resupplying arms. Two weeks later, Libya, Saudi Arabia, and the remaining Arab oil producing states enacted an embargo on oil exports to the United States, quadrupling the price of oil and shocking the oil marketplace. The dangers of energy dependence were clear, and the Nixon administration had no choice but to formulate a plan to protect the United States from future vulnerability.

On February 6, 1974, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger under President Nixon unveiled ‘Project Independence,’ a comprehensive national energy plan to achieve energy independence by the end of the decade. The main goal of Project Independence was to reduce vulnerability. The nation’s “overall objective can be summed up in one word that best characterizes this nation and its essential nature. That word is independence…In the last third of the century our independence will depend on maintaining and achieving self-sufficiency in energy. What I have called Project Independence 1980 is a series of plans and goals set to ensure that by the end of this decade Americans will not have to rely on any source of energy beyond its own.” There were three main components of the plan: accelerating domestic supply, energy conservation and demand management, and emergency programs.

In order to accelerate domestic production, Project Independence called for a diversified approach to fuel this increase in production. The first step was to lease the Outer Continental Shelf of both the Atlantic and Pacific for exploration to tap offshore resources, as well as utilizing naval petroleum reserves to increase domestic oil production. Also, the plan called for the exploration and increased production of Shale gas and increased rates of construction of nuclear energy facilities.

The next aspect of the plan was increasing conservation of energy, effectively managing demand, and being more efficient with how America consumes energy. “We are running out of energy today because our economy has grown enormously and because in prosperity what were once considered luxuries are now considered necessities.”The plan proposed a series of actions to reduce the growth in consumption to two percent annually between 1974 and 1985. These include new efficiency benchmarks for autos, new standards on products and buildings, and subsidies or other incentives to increase residential insulation and energy use efficiency.

The last pillar of the plan was the creation of emergency programs for the current situation and for future ones. The plan called for the creation of an emergency reserve in case of another import supply disruption. Emergency storage was seen as a cost effective way to reduce the impact of an embargo.

Project Independence was logical: increase production, reduce consumption, and plan for emergencies. However the actual implemented policy resulting from Project Independence was wholly different than the plan unveiled by Kissinger in February of 1974. One of the major reasons for this was the reluctance of Congress to implement the plan. Attempts to counteract the worsening energy crisis “were further weakened and counteracted by congressional divisiveness, fluctuating administrative dictums, and the influences of powerful special interests. These impediments to policy formulation, and the legislative entanglements they caused, increased the United States’ vulnerability to the Arab oil embargo and interfered with the implementation of appropriate energy programs.” Near the end of 1973, the National Energy Emergency Act, which the Nixon administration planned to be the cornerstone legislation of Project Independence, was introduced in Congress. Despite causing extremely intense debate on the issue, the bill was never passed, resulting in a major blow to the implementation of Project Independence. The ideological division over economic issues and government intervention in the free market had impeded the passage of a national energy policy.

Another reason for its failure was merely a product of Project Independence being unrealistic and unfeasible. Theoretically, the plan seemed perfect; increase production and decrease consumption. However, with the United States importing over 30% of its consumed energy at the time, closing that gap by the end of the decade was not only unrealistic, but was economically impossible. “Nixon was practically alone in his administration in believing that the nation could realistically become independent of foreign energy sources by 1980. The cost of this achievement would be astronomical, and, in economic terms, suicidal. The administration chose to deal with the embargo and energy shortage initially with symbolic gestures rather than a meaningful plan of action.”

Project Independence was extremely significant, as it was the first major national energy strategy proposed by a President advocating for increased federal involvement with the energy market. The plan set the blue print for a half-century of national energy policies aimed at reducing reliance on foreign energy through a simple formula: increase production, decrease consumption, and provide energy security.

President Gerald Ford, like Nixon, placed energy as a top priority of his presidency. Unveiled in his 1975 State of the Union, Ford’s plan included creating fuel taxes, eliminating price controls, increasing nuclear and coal production, opening the Outer Continental Shelf for oil exploration, promoting the construction of new refineries, the creation of a strategic oil reserve, and the development of synthetic fuels.

I am recommending a plan to make us invulnerable to cutoffs of foreign oil. It will require sacrifices, but it–and this is most important–it will work. I have set the following national energy goals to assure that our future is as secure and as productive as our past: First, we must reduce oil imports by 1 million barrels per day by the end of this year and by 2 million barrels per day by the end of 1977. Second, we must end vulnerability to economic disruption by foreign suppliers by 1985. Third, we must develop our energy technology and resources so that the United States has the ability to supply a significant share of the energy needs of the free world by the end of this century…A massive program must be initiated to increase energy supply to cut demand, and provide new standby emergency programs to achieve the independence we want by 1985.

Ford’s plan was met with significant opposition from Congress. Parts of the plan did eventually make it through Congress as the Energy Policy and Conservation Act of 1975, but the legislation that was passed was far less expansive and effective than that originally proposed by Ford’s plan; a trend that would become commonplace with subsequent national energy plans.

President Jimmy Carter was one of the most forward-thinking presidents in terms of formulating a national energy policy before a second crisis occurred. On April 20, 1977, Carter addressed the nation and unveiled his national energy program. Carter’s plan had three main points; conservation, conversion of our consuming infrastructure to consume more abundant resources and rely less on imports, and investment in research and development of new technologies.

However, Carter’s plan was passed as the National Energy Act of 1978, a weakened version of Carter’s original plan that included much less than his original plan. The NEA was an extremely diluted and much weaker form of Carter’s proposal, severely limiting the impact of the plan. Carter’s plan was limited by a few factors, mainly in Congress, but most importantly the differing ideological factions in Congress that cancelled out, halting congressional progress on Carter’s plan. A lack of congressional support severely hurt the prospect of success of Carter’s first national energy plan.

In early 1979, the United States-backed Shah of Iran was toppled during the Iranian revolution, and with the Shah fell one of the last remaining stable pillars of United States oil supply in the Middle East. The energy crisis had become more grave, and Carter, with the general failure of his first NEP behind him, proposed a second NEP with six main points: creating a clear goal for US energy of not consuming more foreign oil than it did in 1977, limiting imports to 8.5 MMB/D, creating a substantial commitment to alternatives and promising 20% of the nations energy from solar by 2000, a 50% reduction in oil use by utilities shifting to other sources primarily coal, the formation of an Energy Mobilization Board similar to the War Production Board, and lastly, the adoption of a bold conservation program. “Beginning this moment,” as Carter stated in 1979, “this nation will never use more foreign oil than we did in 1977 – never.”

However, once again, Carter’s proposal was met with congressional opposition, and the policy enacted was far weaker than the proposal. “Debate around NEP II coincided with the Three Mile Island nuclear accident, the Iranian hostage crisis, and a second oil crisis, which together had the effect of delaying congressional action until the mid-1980’s, when some provisions of NEP II – such as the windfall profits tax and the creation of the Synthetic Fuels Corporation (abolished by Reagan in 1985) – were eventually passed into law.

When President Reagan took office in 1981, the energy crisis still existed and the effects of the embargo and the Iranian revolution were still being felt. However there was no major shock to the energy market during Reagan’s presidency, but during his eight years, Reagan proposed three national energy plans. These plans too were reactive, but reactive not to a foreign shock, but to the prevailing view on the role of the federal government in the energy market. The Reagan administration believed that the federal government should take a hands-off approach to the energy market, allowing market forces to take over. The energy motto of the administration was “Production, Production, Production,” to achieve independence. Increased production was to come as a result of market forces taking over the energy sector in the United States, and not through an expansive government policy. “The policy of this administration,” stated a member of Reagan’s CEA in their first report to Congress, “is to remove the inconsistency, inefficiencies, and uncertainties caused by inherited policy, and thereafter to facilitate the operation of market forces as the guiding and disciplining constraints shaping investment, production, and consumption decisions in the energy sector.” Reagan stated, “Ending price control is a positive first step towards a balanced energy program, a program free of arbitrary and counterproductive constraints, one designed to promote prudent conservation and vigorous domestic production.”

Reagan’s three national energy policies were very consistent with one another. They all shared the same agenda of removing federal price controls on crude and natural gas, removing many of Carter’s regulations and other federal actions that were imposing on the market, reducing the federal R&D budget relating to energy, and lastly and most generally, “relying on market decisions as the means of charting the nations energy path in preference to government dictates or on a combination of subsidies and regulation.”

Reagan’s set of national energy plans in essence were to create a plan that limits federal involvement and allows the market to takeover control over the energy industry. This policy was reactive to Nixon, Ford, and Carter’s increased levels of federal involvement in crafting national energy plans. With that said, another major implication of the Reagan administrations actions was reversing nearly all of the progress made by President Carter. As will be later discussed, this very policy inconsistency has contributed to the failure of reaching energy independence.

By the time George H.W. Bush took office in 1989, energy issues had retreated to the background of importance for the United States. Still there were no crises, the Middle East was relatively stable, and the price of oil had remained fairly stable. A dispute between Kuwait and Iraq changed all of this. On August 2, 1990, Iraq invaded Kuwait sending the energy markets into shock once again. Energy issues once again entered the forefront of United States policymaking and President Bush responded with a National Energy Strategy (NES) of his own. Contrary to Reagan’s NEP, the Bush’s strategy was in response to a foreign crisis and was subsequently different in nature; once again, the direction of United States national energy policy had changed under a new President responding to a new event. This NES was also a major departure from the Reagan presidency as it advocated for increased federal intervention in the energy markets.

President Bush’s National Energy Strategy had two aspects to it, an environmental aspect and an energy aspect. For the sake of this analysis, the energy aspect will be the main focus. The strategy had seven main energy related components that were similar in nature to Nixon and Carter’s plans: diversify sources of energy supply, increase efficiency and flexibility in energy consumption, reduce the dependence of the U.S. economy on oil while increasing domestic oil production, increase the use of natural gas, increase the production and use of renewable energy resources, increase the use of alternative transportation fuels, and lastly, encourage efficiency and competition in electricity generation and efficient use of electricity power. The Bush NES was one of the few national energy policies to actually translate into a major piece of legislation that was similar to the proposed strategy with the passing of the Energy Policy Act of 1992. The Energy Policy Act contained the majority of the provisions laid out by the national energy strategy, which has been a historical rarity.

So why did President Bush’s NES fall short of independence? The downfall was the changing of administrations. The bill was passed in 1992, the same year the Bush was replaced by President Clinton in the 1992 presidential election. As administrations changed, so did the direction of national energy policy. This lack of continuity made achieving energy independence nearly impossible.

Despite the lack of an energy crisis during the Clinton presidency, President Clinton’s national energy policy was reactive to a new phenomenon, climate change. Although it took Clinton until 1998 to officially propose a national energy strategy, much of the energy policy focus of his administration was on climate-related issues, marking a significant shift in national energy policy once again. Regardless, Clinton’s 1998 national energy strategy still faced major roadblocks. “The administration’s ability to follow through on these proposals was hampered by federal budgetary constraints and congressional opposition.”

President George W. Bush entered office amid pressing energy issues that put energy policy at the forefront of his agenda. Widespread blackouts plagued California and there existed oil and natural gas shortages in many parts of the country. To address these problems, Bush appointed a group led by Vice President Cheney to compose a national energy strategy. The resulting strategy aimed at: increasing energy supply, promoting conservation, efficiency, renewables and alternative energy technologies, promoting the development of unconventional fuels, expanding critical energy infrastructure, and strengthening national energy security safeguards and international relationships to secure supply of oil. This national energy strategy translated into policy quite smoothly, as many of the components of the proposal were embedded in Securing America’s Future Energy Act of 2001, passed on August 2, 2001. Although the attacks on September 11 of course diverted attention from furthering Bush’s national energy policy, Congress passed the Energy Policy Act of 2005, and the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007, both of which incorporated many aspects of Bush’s National Energy Strategy, most notably increased fuel efficiency standards in cars and the increased use of ethanol in gasoline.

The Bush administration has been the most recent to develop and implement a comprehensive national energy plan geared towards energy independence. President Obama has incorporated certain energy policies into other pieces of legislation, such as including the creation of clean energy jobs and subsidies into the stimulus package, but Obama has yet to form and implement a comprehensive national energy policy of his own. The true success of the policies enacted under President Bush are yet to be seen, and much of the success of these policies will rely on President Obama’s decision to either build on the Bush administrations’ policies or take the United States in a new direction by creating a national energy policy.

Ever since the grave dangers of energy dependence became so clear in 1973, eight presidents have promised energy independence and eight presidents have proposed measures to achieve it. Through national energy plans, strategies or policies, each President and his administration has put forth a set of goals and ideas that promising to lead the United States towards energy independence. However, after eight administrations of promises, none of these national energy plans or strategies have been successful, as the United States remains only ~80% energy independent to this day. The past half-century of these failures has been marred by the lack of continuous policy across administrations, lack of congressional support, and the symbolic and seemingly unrealistic nature of the policies proposed.

Today, many believe that American energy independence is truly on the horizon. Massive discoveries of shale natural gas reserves and improvement in oil extraction technologies have sparked a boom in the production of American energy. If American energy independence comes to fruition this time around, it will be the result of a major, unforeseen production boom, and not the result of the unsuccessful policies enacted by the last eight presidents of the United States.