The Modern Puppet State

BY ARI MOSES

It is early February and trash and scorched rubble are littered throughout the street. The clock strikes nine as the sun begins its journey across the sky, but Kiev’s once bustling city streets look as if they are from a ghost town, a mere remnant of their former selves. Offices, schools, and all other manner of business have closed down for the foreseeable future. Rebellion and mass protests have engulfed the city, and taken the state with it.

The sovereign nation of Ukraine is only a few decades old, and foreign influence still looms over the struggling nation. Russia in particular has immense control over Ukraine’s foreign policy, and holds less forceful, yet still recognizable, sway over domestic Ukrainian policy.

Russian Influence

After the formal fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, many of the former Soviet satellite states joined an organization championed by Russia called the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). This organization aims to provide protection for all member nations as well as to prevent the sale and distribution of Soviet era resources and weaponry. In practice, however, Russia uses the CIS to ram a pro-Russian agenda down the throats of member nations, forcing its policies on weak nations that rely on Russia for financial support.

Over the last few years, the Ukrainian government has signaled a desire to pivot away from Russia, towards the European Union (EU). This move would almost certainly diminish Russian political power, a fact that Putin’s government will not accept. They have leveraged the fact that Russia owns the largest percentage of Ukrainian sovereign debt to split Ukraine from the EU. In December 2013, the Ukrainian and Russian governments signed a treaty that provided the struggling nation huge incentives to remain outside of the EU.

Russia maintains a dominant position over regional trade, energy production, and transportation, which it uses to further its own political and economic agenda at the expense of surrounding nations. In effect, Russia controls the region’s energy sector and leverages this reality to influence the CIS nations’ domestic and foreign policy. Using bailout funds and subsidies, the Russian Federation offers its neighbors loan rates the market can’t match in order to make these nations dependent on Russian support. This forces the CIS nations, especially Ukraine, to enact domestic and foreign policy subject to the approval of Russia. Nowhere is this more clear than the recent drama regarding Ukraine’s pivot towards the EU. Ukraine’s attempt to assert its independence from Russian influence was met by a series of incentives intended to bring the nation back into line. The Ukrainian government acquiesced in December 2013, signing a treaty in which Russia offered trade agreements and economic stimulus packages that no other nation could offer. The unspoken subtext was what Russia was receiving in return: obedience.

Incentives

The most important aspect of the 2013 treaty was a clause which allows Ukraine to pay Russia’s state owned enterprise, Gazprom, a price of $268 instead of $400 per 1,000 cubic meters of natural gas—a 33 percent discount. During the 2013 calendar year, Ukraine imported approximately 33 billion cubic meters of natural gas at a price of $352, resulting in a bill of $11.6 billion dollars, or 6.6 percent of the nation’s GDP. As Russia supplies more than half of Ukraine’s natural gas supply, (and Gazprom is responsible for most Russian production) this represents a massive incentive for the government of Ukraine to refuse to join the EU.

Another tool the Russian government uses as leverage over Ukraine is its status as the largest investor in Ukrainian securities. Russia has more than $30 billion invested in national securities and $15 billion reserved for the purchase of new debt. Of course, this debt support is conditional on the existence of a pro-Russian government in Kiev, and its removal would cripple Ukraine’s economy in the short term.

Sanctions

When carrots fail, Russia turns to sticks to beat its neighbors into submission. Russia supplies 25 percent of the EU’s natural gas, and almost 80 percent of this natural gas flows through pipelines in Ukraine, which Russian gas companies pay tariffs to use. In the past, when Gazprom and the Ukrainian government have disagreed, the Russian oil giant has refused to utilize Ukrainian pipelines, denying the nation crucial tariff revenues. Instead, it has opted to take a loss and supplied its gas to Europe through less efficient methods.

Russia uses its trade with Ukraine in a similar fashion. Although Ukraine has diversified its imports and exports over the last few years to reduce its dependence on Russian trade, Ukraine’s largest trading partner remains, undoubtedly, the Russian Federation. The entirety of Europe, the second largest consumer of Ukrainian exports, purchases only 29 percent of Ukrainian exports; Russia is responsible for 40 percent. Similarly, 15 percent of Ukrainian imports arrive from Russia, the largest amount of any nation exporting goods to Ukraine.Because Russia sustains a much larger economy, it can afford to sell its resources at a subsidized rate in order to keep the CIS countries in its sphere of political dominance. Whenever the governments of Ukraine and Russia drift apart ideologically, Russia either slows trade with the nation or increases the prices on necessary exports to it, while refusing to spend more on Ukrainian products. Since Russia is the single largest entity that trades with the former Soviet satellite state, any disruption in trade between Russia and Ukraine cripples the Ukrainian economy; meanwhile, such interruptions barely register on the massive scale of the Russian economy.

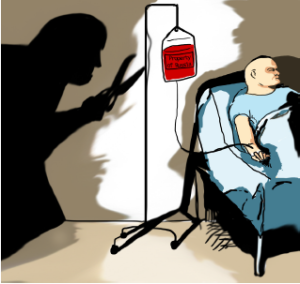

These powerful incentives explain the Ukrainian government’s reluctance to turn away from Russia. Yet despite the short-term economic logic, the reversal of Ukraine’s pivot towards the EU remains a highly unpopular move and has resulted in months of protests, both in Kiev and across the country. Many in Ukraine believe that Russia deliberately keeps Ukraine on the economic equivalent of life support in order to ensure its subservience, whereas the EU would provide the nation with the proper investments to expand the Ukrainian economy, adding jobs and raising incomes across the country.

Gazprom and the CIS Nations

Over the past decade, Gazprom, on behalf of the Russian government, has been purchasing large natural gas reserves and fields in CIS nations, most notably in Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan. Such large energy sector purchases are possible because many CIS nations remain heavily indebted to Russia. Belarus was forced to sell a profitable national asset, the Beltransgraz pipeline, to Russia because the nation was unable to pay its loans back to Gazprom. Similarly, Kazakhstan and the other nations in the region are too poor to build their own pipeline networks and are wholly dependent on Russian pipelines to transport gas, oil, and other resources out of the country.

Russian activity in Kazakhstan provides a good example of how profoundly this influence can set a nation back. Over the past decade, the Russian government has been using its influence to combat the growing power and reach of foreign energy companies investing in Kazakhstan. Through threats to increase pipeline access fees or by bribing powerful local business executives, often by placing them on the boards of prominent Russian energy businesses, Russia has both increased its own investment in the Kazakh energy sector and reduced the country’s attractiveness to foreign investors. This weakens the Kazakh economy in the long term and makes it more dependent on Russia. In turn, this new reliance on favorable relations with Russia has forced Kazakhstan to sell its resources at artificially low prices to appease the Russian government, which decreases Kazakhstan’s chances of future autonomy and economic prosperity.

The Puppet State

Ukraine may be legally independent, but it remains dependent to and subject to the power of the Russian Federation. Whereas it once was legally a territory possessed by the Tsardom of Russia, then the Russian Empire, and finally the USSR, today Russia seeks to dominate Ukraine through economic measures, under the guise of friendship and benefaction. A nation that must have its foreign policy approved by an economic benefactor, however, has lost its sovereignty. It is a nation subject to the whims of a more powerful regional player. As it stands today, the government of Ukraine is nothing more than a puppet of the Russian government, a mere façade to the global community.

This unjust power grab by the Russian government has whipped Ukrainian citizens into a frenzy of protest and unrest. The statement is clear: no longer will the Ukrainian masses tolerate Russian dominance over their foreign and domestic policy. Whether the dissenting Ukrainian people will be able to break their nation away from Russian influence, however, remains to be seen. They may have the passion, but as we have observed, Russia has the money.