The Raze of Ruby

BY GRACE PORTELANCE & SHIVANI DESAI

Rubelmann Hall stands proud and tall, truly the gem of the South 40. Built in 1958, she is the oldest of her kind and has given a warm home and a comfortable bed to many generations of Wash U students. As residents of Ruby, we know her shine may be a little tarnished, her walls may be more run-down, and her amenities might be somewhat limited compared to those of her friends Umrath, Koenig, and Danforth, but her close community and cozy layout are still loved by many. However, as summer quickly approaches, so too does Ruby’s impending demolition. Soon, a sparkly new dorm will rise from the dust of our historic and well-worn building, and Ruby will become Wash U’s most recent fallen soldier in the quest to modernize the 40.

Claiming that Ruby should not be torn down is difficult to argue on principle alone; while most people (ok, maybe just us) appreciate the humble charm of this old building, it is simply the prerogative of the school to tear down and rebuild whatever structure they see fit, especially one over fifty years old. However, knocking down and rebuilding a dorm that is still fully functional, capable, and loved has massive implications for the future of underclassman housing at Wash U and speaks to a larger pattern. It is one thing to renovate a dorm in desperate need of repair in order to cater to the same set of students it did previously: those who would rather live in traditional housing for financial or community-building reasons. But it is a completely different story to reconstruct the building in accordance with the new choice look of campus: sleek, modern, and most of all, expensive.

When it comes to the price tag on new Wash U residential buildings, one could argue that it is natural for a university to want to continuously improve its housing and amenities. After all, Wash U is well known and well regarded for having some of the nicest housing and food options. The school has repeatedly defended its actions by arguing that it is simply accommodating the requests of its students. Yes, the surveys prove that the dominant voice of the student body is asking for more modern dorms, individual bathrooms, and palace-sized common rooms, but in doing so, they are drowning out the fainter voices of those who cannot afford to pay for such lavish living. The university is catering to the student body it has now, not the one it professes to be trying to attract. And the options for affordable housing are getting slimmer and slimmer, a fact that marginalizes the small minority of students who fall into lower income brackets and thrusts the absolute lack of socioeconomic diversity present on campus into the spotlight once more. It seems contradictory that the school claims an inviting environment for low-income students, yet only responds to the needs of the higher income population.

The gradual “modernization” of residential housing also removes the dorm-life option that most of our parents fondly associate with their college experience: shared bathrooms, small rooms, third-floor walk-ups, and true communal living. It seems that our school is putting a great deal of money towards making such an experience an obsolete remnant of the past. In essence, the message Wash U is sending reflects not only a rejection of the traditional, outdated dorms, but a rejection of the type of students who prefer them. Modernization changes not just the prices of housing, but also the culture of campus and the variety of experiences available to students. Personally, we both felt at home with Ruby’s simplicity. It was comforting to know that attending a school with incredibly high tuition and low socioeconomic diversity didn’t mean there weren’t places to live cheaply and traditionally. Less expensive, traditional housing is not just an option on campus, it is a necessity: it conveys a crucial message of inclusion and adaptation to the needs of a population of varying wealth and class.

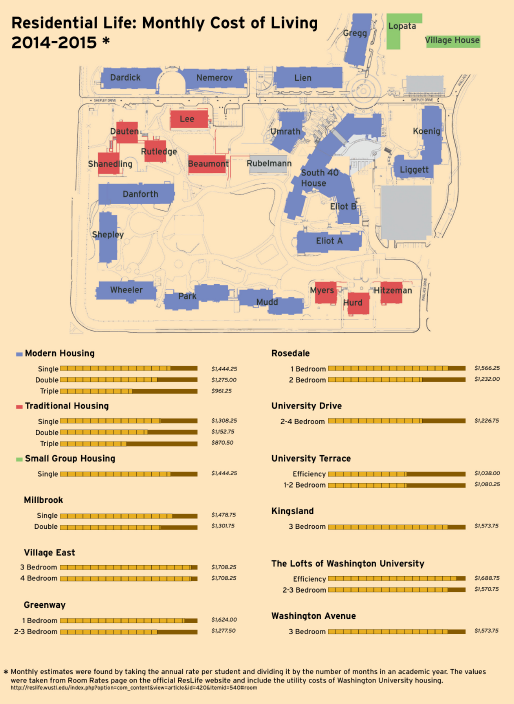

This problem isn’t just one facing incoming freshman; it affects the entire 40. As incoming sophomores, we are seeing firsthand the struggle of choosing housing set-ups when they are so dramatically allocated by price. For the 2014-2015 school year, the cheapest housing available to second year students is a traditional double, at $9,222 a year. A modern single, a common option for sophomores, is $11,554 annually. This $2,332 difference is considerable and can make a crucial difference. But it is not just a matter of numbers: personal feelings, relationships, and more broadly, a large component of the sophomore experience, can rely on upcoming housing plans and all of the complicated arrangements surrounding them. Consider a scenario of a group of friends deciding where to live for their sophomore year. If one friend cannot afford to live in a modern dorm, she is forced to face the awkward situation of either explaining her financial constraints to the potential roommates, or having to split off and room with others in a similar financial situation: a sort of segregation of the student body based on willingness and ability to pay. And the ramifications stretch further than that: as some traditional residencies such as Myers are being offered only to freshmen next year, traditional options are being taken away from sophomores. With the precarious housing lottery system, a student who genuinely needs traditional housing could end up relying purely on the luck of the draw. As junior and senior years approach, low-cost housing options decrease further as the Village and off-campus apartments become nearly the only choices. In our opinion, it is evident that something needs to be done in order to make affordable housing accessible and common at Wash U.

One potential solution is to adopt the system that many schools that support need-blind admission policies use: flat rate rooming prices. At Pomona College, an academic peer of Wash U, current rooming rates are a flat $8,200 per year. This is similar to the annual rate of a modern triple at Wash U, but housing quality is decided solely by lottery, with no respect to price. Vanderbilt University utilizes a similar flat rate policy to Pomona, and on their Housing and Residential Education website they give the following rationale for charging one fee for all students and all types of housing:

•“Ease of budgeting for college expenses” or the notion that housing prices should be predictable for all students.

•“Equal opportunity to experience any of our residential communities” which allows students to choose their community in a fair selection process irrespective of wealth.

•“Peace of mind and focus on academics,” or the idea that housing prices shouldn’t be a source of anxiety or a distraction from college life.

Are these not principles Wash U holds? It seems that our school views embracing and enhancing socioeconomic diversity as a very one-dimensional process; by simply admitting more Pell Grant recipients, the school hopes the percentages on the pie chart will shift and Wash U will suddenly, magically, transform into a place that welcomes those of all backgrounds. By assuming this, our school is ignoring the factors that make attending Wash U not only economically difficult but also culturally misaligned for low-income students. High costs of living and a wealthy student body are fixable problems (if the school would someday, maybe, make a strong effort to fix them), but also of great concern is the culture we are creating. The real question becomes: is the demolition of Ruby perpetuating a destructive pattern, or helping us progress in the direction we hope to move? We will miss Ruby for many reasons, some of which are personal. Our best memories from freshman year took place in those crooked, winding hallways and communal bathrooms.. However, regardless of whether one lived there or not, we should all mourn the impending loss of Ruby as the big, concrete box in the middle of the South 40 that committed the sole crime of not being “trendy” enough for the new, sleek image of the school. I suppose the next question is, are we, the students who want to maintain an inclusive, welcoming culture, guilty of the same offense? Are we simply behind the times, too naive to understand that “new is always better?” It seems that Wash U has inadvertently created a self-sustaining pattern, begging us to ask if low income students—with their limited options and need for affordability over style—are actually the ones Wash U blames?

It may seem like we are making a fuss over a dark, crumbling, and run-down building, but the raze of Ruby is indicative of a much larger battle currently raging on our campus: Wash U’s socioeconomic crisis. In terms of housing, campus polls cited by the administration are being filled out largely by high-income students, who will usually request a certain level of luxury. However, by only listening to those requests, Wash U is not only drowning out the voices of its minority low-income students, it is also ensuring the fact that future low-income students may feel marginalized as well. When lower-income prospective students visit Wash U, they may visually sense the culture of “modernization” and luxury present on campus and feel alienated, thereby eliminating Wash U from their future and eliminating a chance for greater diversity on our campus. This cycle will continue until someone or something breaks it. We call upon Wash U to rise to the challenge.