The Misunderstood SAT

No obstacle along the college admissions gauntlet attracts so much criticism as the SAT. Scores on the SAT or ACT are second in importance only to grades in determining college admissions decisions, and by the time students take the test, there is little they can do to dramatically improve their performance. It is therefore unsurprising that the College Board’s recently announced changes to the exam reawakened discussion about the role that this test plays as a gatekeeper to the nation’s selective colleges.

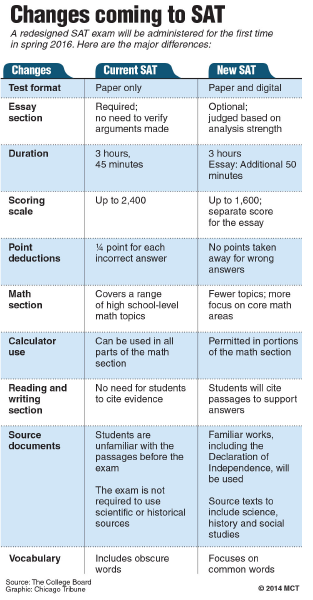

The planned changes correct many of the problems introduced by the poorly conceived 2003 revision of the test and are generally worthy of praise. The essay section, which currently allots only 25 minutes to the task of developing a coherent persuasive argument, will become optional and provide more time. The verbal and math sections will once again carry equal weight; currently, the Math section only counts for 1/3 of the test’s total points.

But these changes have not been enough to quiet the army of critics that insists that the SAT perverts the college admissions process, favoring wealthy students who can afford expensive private tutoring. These critics raise valid issues, but should direct their criticism towards the college admissions process in general rather than the SAT specifically.

As a private SAT tutor who has helped many students perform better on the test, I have come to understand clearly what the SAT does and does not measure. Among other things, an SAT score accurately reflects students’ abilities to read quickly, to understand what they read, to think logically, to use a large vocabulary, and to recognize and correct common grammatical errors. All of these skills are critical for success in college and in many professions beyond. Thus, learning to score higher on the SAT is really about becoming a better reader, editor, and logical thinker.

While tutoring does include some discussion of test-taking strategy, strategy alone will get SAT-takers nowhere; what matters is skill in the areas that the SAT measures. Tutoring can boost a student’s score, but it cannot overcome fundamental weaknesses in reading and math ability. For example, scores on the vocabulary section are best improved by reading widely over many years.

Furthermore, tutoring accomplishes nothing that a motivated student cannot achieve on his or her own. Excellent materials to prepare for the SAT are already freely available online, and the College Board is partnering with Khan Academy to create even more. Tutoring simply enforces a regime of preparation if students are unable or unwilling to do so themselves.

Is it unfair that students with working parents who cannot afford a tutor must be more disciplined to achieve the same academic results? Of course. However, the same inequity affects every part of a student’s academic career from his or her earliest educational experiences. After all, children who have had a parent stay home to make sure that they do their homework enjoy an enormous and unfair advantage, and tutoring can extend far beyond the SAT to encompass academic subjects as well.

This does not mean that the SAT should not inform admissions decisions. High schools vary greatly in academic rigor and level of competition, and SAT scores allow students to prove to colleges that they have the core reading and math skills needed to succeed – even if their grades are inferior to those of students at less demanding high schools. Conversely, a particularly low SAT score can serve as a legitimate red flag that, despite high grades, a student may not be sufficiently prepared.

Instead of criticizing the SAT for being an imperfect measure of intelligence, which it never claimed to be in the first place, champions of improving access to college should focus on encouraging a holistic approach to admissions that recognizes that students from more advantaged backgrounds have had greater support in their academics across the board, not just in learning the skills needed to succeed on the SAT. Inequalities in the admissions system are not the fault of the SAT, but rather of those who are unwilling to make considerations for disadvantaged students.