Crises of Nationalism

BY JOE LENOFF

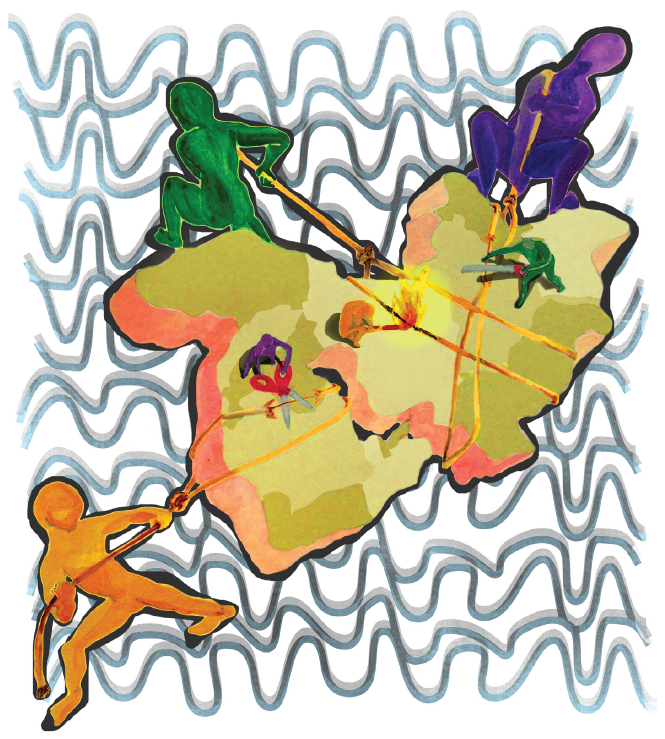

In the aftermath of the First World War, the European states dismantled the Ottoman Empire and designed a system by which the Middle East would be carved into separate states ruled by people the Europeans themselves hand-picked. Although there were a series of agreements between the Europeans, such as the Sykes-Picot Agreement in 1916 and the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923, after the end of the protectorate system and the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, the map of the Middle East looked much the same as it looks today. Over the course of roughly the last 60 years this system of dividing land and power has been challenged, most notably by Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser’s pan-Arabism in the 1960s, but the system has never had as many challenges, across as much land and as many cultures, as it has had recently. The peoples of the Middle East are rejecting the states carved for them by Europe—along with the very idea of Western nationalism—in favor of a narrower, more sectarian view of loyalty. Today, the physical lines separating the states of the Middle East are less important than the psychological lines separating sects.

Most Westerners believe in state-nationalism, that is, the setting aside of one’s loyalty to one’s own personal nation, tribe, or sect in deference to the state. That is why many Americans call themselves African Americans or Jewish Americans. The subordinate adjective precedes the dominant noun. Peoples of the Middle East, however, are increasingly shifting to sectarian nationalism, which is just the opposite. A Kurd living in Iraq, for example, is an Iraqi Kurd. Because sectarian nationalism is flourishing today in the Middle East, many Middle Eastern states are under great strain by their individual sects and are finding it increasingly difficult to maintain state control and citizens’ safety. Many states are under pressure to separate into multiple smaller nation-states, and many are engulfed in bloody civil wars, but most can trace their struggles back to sectarian nationalism. Nowhere is this more evident than Syria, the Kurdistan region, and Iraq.

SYRIA

Since nearly the beginning of Islam, Damascus and its surrounding area have been a crucial pivot-point for the Middle East. This is no different today, with the Syrian conflict driving a wedge further between differing Islamic sects. The Syrian conflict is typically described as government vs. rebels, but that does not tell the whole story. A more telling way to describe the Syrian conflict is Alawites and Shia vs. Sunnis. Alawites are an offshoot of Shiite Islam, and both sects share similar grievances against Sunnis. Syrian President Bashar al-Assad is Alawite, and most of all the important government positions, including the military, are held by other Alawites. Though Alawites only make up about 10 percent of the general Syrian population, they make up about 75 to 80 percent of the officers in the Syrian military. Iran, a Shiite state, and Hezbollah, a Shia terrorist group, are providing the Syrian government with military armaments, expertise, and troops for geopolitical reasons, but those reasons also align within the larger sectarian battle between Shia and Sunnis.

On the other hand, the Sunni side of the Syrian conflict is an amalgam of small and competing militias. Some Sunni rebels are Syrian, and some are secular, but there are also mujahidin coming from around the world to fight Assad in what they believe is a holy war over the direction of Islam. People are coming from around the world to ensure the success of their particular sect. However, even within these religious categories there is little unity. Each lieutenant does what he believes is best, resulting in mayhem for Assad’s competing armies, but also for those who are trying to organize the rebel forces. The Syrian National Coalition and its Free Syrian Army were once considered the best and most legitimate umbrella organization, but have since fallen by the wayside in the wake of failed peace negotiations in early 2014.

The Westerner’s idea of “legitimacy” is becoming less and less important. What is important is the ability to affect change on the ground, and that ability comes from the force that foreign funding provides. Qatar provides aid for the sect that it believes in: extremist Islamists; Saudi Arabia provides aid for the sect that it believes in: moderate Islamists; and the United States provides non-lethal aid for the sect that it believes in: those whose interests and perspective are aligned with Western interests. Even among the rebels there is sectarian conflict.

The Syrian conflict is an outlet to express and exacerbate the grievance between Sunni and Shia. The two sides are not fighting for the control of the Syrian government. Some smaller groups may be, but state control is a means to the larger goal of defending their particular sect and their sect’s worldview. The competing sects are reasonably afraid of the opposite side committing some degree of ethnic cleansing after their victory. It is literally an existential battle for each sect against the other. It is also a war of ideas and religion, as well as a proxy battle between Iran, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia in a bid for sectarian dominance.

KURDS

Moving north and east, the Kurdish people provide another example of sectarianism. Kurds were the great losers of the post-World War I separations. They found themselves without a nation-state of their own, and were instead split between Turkey, Syria, Iraq, and Iran. However, they have taken advantage of the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003 along with the Syrian conflict and current Iraqi civil war to single themselves and their needs out as unique and significant. Iraq’s post-invasion constitution established the “Kurdistan region” (areas where Kurds live) as semi-autonomous and under the auspices of the Kurdistan Regional Government. Kurds were given their own police force and military, the ability to levy taxes, and the ability to revoke federal Iraqi law within the Kurdistan region. This in itself is a significant example of a Middle Eastern state subordinating state-nationalism in favor of sectarian-nationalism. However, the Syrian Conflict and the current civil war in Iraq have provided the Kurds with even more autonomy. The pesh merga, the Kurdish military, fight solely for the safety of the Kurdish regions. They do not secure the general Iraqi borders at any point except for those that connect to the Kurdish regions of Syria. When the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), an ultra-Islamist terrorist group formerly allied with Al-Qaeda, invaded Iraq, the Iraqi and Syrian Kurds did not engage until ISIS attempted to take Kurdish lands. They simply do not view it as their battle to fight. Western Iraq is seen as Sunni land, not Kurdish, and therefore not worth fighting for.

IRAQ

Arab Iraq is also under sectarian strain. Iraq was created “artificially” by the Europeans after World War I, but the 2003 U.S. invasion and subsequent occupation destroyed the state’s stability. Civil war has ravaged the country for years, and, consistent with recent patterns, it is split between opposing sects. In this case, eastern Shia have been battling western Sunnis in a horrible civil war for nearly a decade. According to Iraq Body Count, since President Bush declared “Mission Accomplished” in Iraq on May 1, 2003, anywhere from 120,000 to 130,000 Iraqi civilians, both Sunni and Shia, have died in the subsequent violence.

In addition, as of publication, Iraq has been unable to form a government since elections were held in April 2014. Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, the first Shia in power in Baghdad since before the Ottoman Empire, has been in power since 2006 and has instituted policies largely to the benefit of Shia, and to the dismay of Sunnis and Kurds. Many Sunnis and Kurds do not want him to be sworn in again as prime minister, but his coalition received the most votes, so there are now sectarian electoral battles to add to the sectarian physical battles.

The combination of war weariness and political distrust led the Sunnis of western Iraq to succumb to ISIS’s invasion and subsequent declaration of independence as the Islamic State. Battles were hardly fought for the land, and now ISIS controls large and ever-growing swaths of the Arabian and Syrian desert. Using superior knowledge of local tribal affiliations and allegiances , ISIS was able to form an unbreakable network in the area and rise essentially uncontested to power. Ironically, in their mastery of sectarianism, ISIS was able to create the beginnings of a state.

Turning the lens inward, it should be noted that the United States is also somewhat complicit in sectarian politics and sectarian affiliation. For example, our national Republican Party is predominantly white and Protestant and over 90 percent of African Americans voted for Barack Obama for president in both of his two elections. Still, more often than not, the American people differentiate themselves politically on ideological grounds (big government vs. small, socially laissez faire vs. restrictive). We do not separate our politics into ethnic or tribal affiliation, and our politicians act with an eye for the good of the state as a whole, not for the politician’s own sect or ethnic distinction. We also go to war for ideological grounds. For example, the United States may have happened to be fighting North Vietnamese in the 1970s, but that was not the war’s purpose. The purpose was to battle the ideology of communism. Americans differentiate themselves and fight for ideological reasons. Increasingly, peoples of the Middle East are differentiating and fighting for sectarian reasons.