License to Destroy

BY SONYA SCHOENBERGER

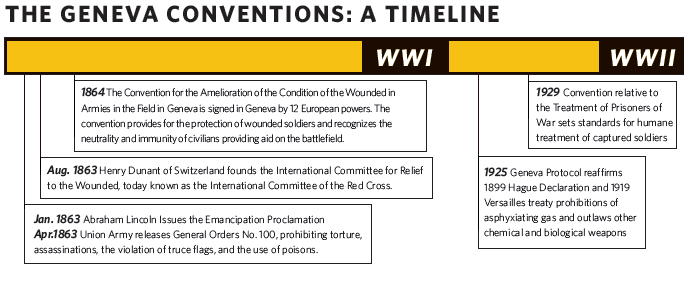

In 1863, President Lincoln’s critics denounced the Emancipation Proclamation as a barbaric violation of the laws of civilized warfare. By emancipating slaves behind Confederate lines, they argued, the Union had utterly dispensed with the restraints of enlightened military conduct. Northerners and Southerners alike viewed the proclamation as nothing more than the incitement of a wholesale slave rebellion that would give rise to the indiscriminate slaughter of white women and children.

Such fears soon proved unfounded. News of emancipation took months to reach many southern blacks, and when it did, no large-scale rebellion ensued. But Lincoln’s detractors were correct in one respect—announcing the freedom of enemy slaves was, ultimately, a war tactic.

In Lincoln’s Code: The Laws of War in American History, John Fabian Witt identifies the Emancipation Proclamation as a key turning point in both the Union war strategy and the American approach to wartime justice. The act marked a transition from adherence to European Enlightenment ideals of limited war—which placed constraints upon the conduct of both warring parties, no matter how ‘just’ their cause—to an escalation of military intensity bound up in the conviction that the Union’s cause was unambiguously just. In freeing Confederate slaves, Lincoln expanded the reach of the war effort beyond the battlefield into the heart of private southern life. While Confederates cried barbarism, Lincoln and his cabinet felt that the profound justice of their cause—the preservation of the Union— warranted a reinterpretation of contemporary norms of ‘civilized’ combat.

Lincoln’s Code presents a genealogy of the laws of war in American history that sweeps from the decades leading up to the Revolutionary war to the United States’ counterinsurgency campaign in the Philippines at the turn of the 20th Century. The focal point of Witt’s narrative is the Civil War, and the role played by Lincoln, his advisors, and jurist Francis Lieber in setting the moral tone of wars to come.

In 1863, Lieber and his team of assistants codified a set of rules that would mark an enduring doctrine in American and international laws of war. Under the name of General Orders No. 100, these rules were widely disseminated within both continental armies and across the Atlantic. Though ostensibly created to restrain the violence of war, General Orders No. 100 was, according to Witt, ultimately a tool to help the Union win the war. It endowed warring powers with a broad license for violence, asserting that, while armies should seek to limit collateral damage and gratuitous destruction, military necessity would justify departures from humanitarian principles in a broad range of situations. Witt describes Lieber’s interpretation of “military necessity” as providing “both a broad limit on war’s violence and a robust license to destroy.” While Lieber condemned superfluous violence, he condoned all violence that could be interpreted as rationally productive within a broader war plan, believing that profoundly just ends licensed unscrupulous means. As quoted by Witt, Lieber believed that “The more vigorously wars are pursued… the better it is for humanity.”

Lieber’s code came to define the US approach to war through the turn of the 20th century, and provided the foundation for 21st century American legal codes, international treaties, and conventions concerning the laws of war. Witt’s careful study of the historical conditions that gave rise to the laws of the Civil War thus sheds light not only on the judicial frameworks of 19th century, but also on the legal underpinnings of our contemporary approach to warfare.

Witt highlights the perennially fraught distinction between crime and warfare throughout Lincoln’s Code, and describes their ultimate intersection as the 19th century gave rise to the concept of the war crime. He also emphasizes an enduring historical tension between two cherished American values: humanitarianism and justice. Witt intimates that Americans’ conviction in the infallible justice of their national narrative—American exceptionalism— militates against the ideal of universalist humanitarianism.

Introducing his monograph, Witt notes that the seeming contradictions between American conduct and civilized warfare—from the genocide of indigenous populations to the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki—are not, in fact, contradictions. The American laws of war were written not to constrain, but to augment and solidify power. American exceptionalism has profoundly shaped both the creation and interpretation of the laws of war in history. While Witt’s 18th and 19th century case studies highlight themes that continue to be central to modern discussion of war, Witt concludes his narrative just as the United States stepped over the threshold of empire—an important transitional moment in the United States’ relationship to the laws of war.

Witt highlights the American experience in the Philippines at the turn of the 20th century as a harbinger of a new kind of war, in which armies unmoored from a righteous cause— like preserving the union, or freeing slaves—would adopt increasingly violent tactics. “A dubious war of empire,” Witt explains, “had detached the code from the righteous cause that had produced it.”

Witt does not further develop these allusions to the corruption of the laws of war during a century of American imperialism. While he plays with rhetorical questions about whether laws of war can ever transcend the interests of powerful nations, these too go largely unanswered. Witt’s narration of the laws of war in American history glosses over the century and a half in which the United States played its most pivotal role in global affairs and international humanitarian law.

Despite its premature denouement, Lincoln’s Code provides important historical context for themes that continue to animate discussions of appropriate use of force today, from debates over torture to the distinction between legitimate and illegitimate combatants. Witt powerfully and painstakingly demonstrates that, just as the laws of war shaped history, history gave rise to the laws of war. The values enshrined in current norms and codes are not ideals forged in a vacuum but products inextricable from the power politics of the past and present.