Fascists and Futurists: The Art of Violence

BY GABRIEL RUBIN

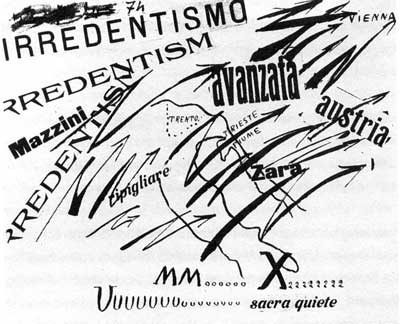

Typically, when someone crashes his car into a ditch, he does not tend to exclaim, “I felt my heart pierced deliciously by the red-hot iron of joy.” Unless, of course, that car crash leads him to create a whole new genre of art. The poor driver in question, the Italian poet F.T. Marinetti, was so invigorated by the sensation of driving—and crashing—his car, that he, along with a fiercely motivated cadre of young Italian artists, spent the next 35 years (1909-1944) creating the movement known as Futurism. Marinetti and the Futurists saw the rapid mechanization and industrialization of Italy as the salvation of their civilization, long dismissed as backward and decadent. Their glorification of modernity, specifically fast-paced urban life and “The Machine,” would make the Futurists—restless ideologues eager to purge Italy of its antiquated traditions in favor of a new order—useful allies for Mussolini’s Fascist regime.

As Marinetti saw it in 1909 (when he wrote his first “Futurist Manifesto”), Italians had to choose between either the “Mythology and Mystic Ideal” of the Romans or “the sun’s red sword, slashing through our millennial gloom.” The choice, apparently, is obvious. Marinetti’s “red sword” was not merely flowery imagery. Item number nine of the Manifesto’s principles states that the Futurists viewed war as “the world’s only hygiene,” and only the “destructive gesture of freedom” could truly wash away the stain of previous generations.

The Futurists got the modern war of their fantasies in 1914, but the (somewhat pyrrhic) Italian victory in World War I only set the stage for reshaping Italian society. To mold their rebooted civilization, the Futurists needed a counterpart in the political realm who embraced the same ideals of a reborn, strong, modern Italy. They found an amenable patron in Mussolini and the rise of the Fascists in 1922; the Futurists had always rejected liberal democracy as dithering and effeminate.

The “effeminate” was the enemy; it prevented Italy from achieving its full potential. The modernity of the Fascists and the Futurists had no place for feminism or for women with agency. Aggression, audacity, courage—these were the “manly” attributes prized in their ideology. Marinetti depicted women as passive, “immobile” creatures whose “moralism” had succeeded in corrupting literature and art.

Though they painted themselves as scions of a new age, the Fascists and Futurists were really ultra-conservatives ideologically. Industrialization and the trappings of modern capital were the price of entry to the club of elite nations, so Italy could either adapt and “advance” or be left behind as an economic and cultural backwater. The genius of Mussolini and Marinetti was to harness the energy from the rapid socioeconomic changes to fundamentally reshape Italy’s national ideology while reinforcing the traditional hierarchy that had governed Italian civilization for centuries.

Reconciling the chauvinistic conservatism of Fascism with the blitzkrieg speed of modern industry poses fewer problems than might be expected. Slavoj Zizek, in his examination of Nazi propaganda, explains that in times of huge disruptions to the social order (from agrarian to urban, religious to secular, manual to mechanized), the populace is highly susceptible to the appeal of both nostalgia and utopia. At first glance those two concepts seem antithetical, but both rely on the myth of the supremacy of the nation.

The Fascists appealed to nostalgia for Italy’s (largely distorted) history as an imperial power, and even invaded Ethiopia (“Abyssinia”) to show that the nation had returned to its previous might. The Futurists referenced a more primordial and utopian yearning, glorifying the basest masculine attributes and stroking the chauvinism of the Italian Man. Surely only he had the power to master the machine and use it as a tool in his conquests. By using this power he could create a new Italy, one that would equal or surpass even the highest points of the nation’s history. The Nazis used the same line of thought, presenting Hitler’s Germany as the Third Reich: simultaneously an original creation and the perfected form of ancient predecessors.

Though the Futurists’ rise preceded the Fascists’, they were felled by the same sword. War and modernity had not elevated Italy to an exalted position among nations; it had led to the 1943 Allied bombing of Rome and a brief but brutal Nazi occupation of northern Italy. Marinetti had bound his artistic movement to the regime, even serving as a member of Mussolini’s Accademia d’Italia. The movement died with the collapse of Mussolini’s regime towards the end of World War II. Even in 1909, though, Marinetti knew his movement would have to end with fiery rage and destruction—and this would be a sign of its success: “Art, in fact, can be nothing but violence, cruelty, and injustice.” Modernity in Fascist Italy ended up looking apocalyptic rather than utopian—instead of new creation, the storied nation found itself with yet more ruins.

9 Comments

Join the discussion and tell us your opinion.

[…] Slavoj Zizek, in his examination of Nazi propaganda, explains that in times of huge disruptions to the social order (from agrarian to urban, religious to secular, manual to mechanized), the populace is highly susceptible to the appeal of both nostalgia and utopia. At first glance those two concepts seem antithetical, but both rely on the myth of the supremacy of the nation. [source] […]

[…] as scions of a new age, the Fascists and Futurists were really ultraconservatives ideologically,” writes Gabriel T. Rubin. Again, sound familiar? In their never-ending quest for progress at any cost, today’s companies […]

[…] as scions of a new age, the Fascists and Futurists were really ultraconservatives ideologically,” writes Gabriel T. Rubin. Again, sound familiar? In their never-ending quest for progress at any cost, today’s companies […]

[…] of a new age, the fascists and futurists were actually ideologically ultraconservative", wrote Gabriel T. Rubin. Again, sounds familiar? In their never-ending quest for progress at all costs, today's […]

[…] as scions of a new age, the Fascists and Futurists were really ultraconservatives ideologically,” writes Gabriel T. Rubin. Again, sound acquainted? Of their endless quest for progress at any price, in the present day’s […]

[…] of a new age, the Fascists and Futurists were really ultraconservatives ideologically,” writes Gabriel T. Rubin. Again, sound familiar? In their never-ending quest for progress at any cost, today’s […]

[…] as scions of a new age, the Fascists and Futurists were really ultraconservatives ideologically,” writes Gabriel T. Rubin. Again, sound familiar? In their never-ending quest for progress at any cost, today’s companies […]

[…] που δημοσιεύτηκε στο περιοδικό Washington University Political Review. Ο Gabriel T. Rubin είναι αρθρογράφος της The Wall Street Journal. […]

Fascism is NOT “ultraconservative.” Fascism grew out of Socialism. It is National Socialism favored over International Socialism. It took the less hypocritical line by acting like it believed its Darwinism too. However, only the purest of hypocrites, cowards, and lunatics can be Darwinist and Socialist at the same time. Hitler was such a psycho.