Cruel and Usual

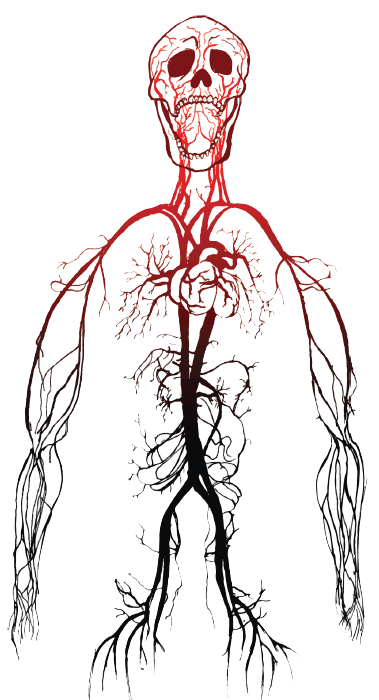

In a harshly lit room, a physician, an employee of the state, twists open three valves in sequence. Lethal chemicals, often from an undisclosed source, rush down narrow plastic tubing into the veins of a condemned inmate. Within a few minutes, the inmate’s heart stops beating, leaving the body of the vicious criminal motionless, and perhaps creating a sense of closure for those close to the victim. This is the process used in the United States to execute death row inmates. Usually it works.

For many in the United States, lethal injection can absolve the possible feelings of guilt surrounding the use of capital punishment; it is much easier on the conscience to conduct executions silently through a sterile needle than via hanging, electric chair, or firing squad. In theory, it’s an ideal process—one or multiple drugs will, in order, knock out the inmate, tranquilize his muscular system, and ultimately induce cardiac arrest. But in practice, lethal injection often doesn’t work as intended—and the consequences can be disastrous.

In the past six months there have been two high-profile lethal injection executions in the United States that have been botched. Joseph Rudolph Wood III, an Arizona double-murderer, struggled for air for the last two hours of his life in July. Just a few months earlier, Oklahoma inmate Clayton Lockett’s execution was stopped after he began to physically struggle on the gurney. Lockett eventually died within an hour of being injected with the drugs. The details of his struggle are gruesome and horrifying.

Last moments lasting hours? Gasping on the gurney? Such unintended but disturbingly frequent side effects of lethal injection violate the most fundamental human rights. A nearly instantaneous death by firing squad would be preferable to the unreliable and convoluted mechanism of lethal injection currently employed; perhaps that’s why infamous killer Ronnie Lee Gardner elected to die by firing squad in Utah in 2010. Despite the firing squad no longer being an option for newly convicted felons, Gardner was grandfathered into the option thanks to his 25-year tenure on death row. His death by bullets was seamless, his pain minimized and his likely mental anguish fleeting.

The death penalty exists as a relic of the Hammurabian “eye for an eye” mentality that has been abandoned by most developed nations. However, these countries hold critical positions in the United States’ global trade network, and for a while provided the drugs used in lethal injections. In 2011, pharmaceutical giants Hospira and Lundbeck ceased exporting sodium thiopental and pentobarbital, two standard elements in the U.S. prison euthanasia cocktail. The former corporation is American but produced sodium thiopental in Italy, while the latter is Danish. Later that year, the European Union prohibited all exports of lethal injection drugs, including some that have other medical benefits. Pennsylvania, Texas, Oklahoma, and other states have been under fire for replacing these international sources of sodium thiopental and pentobarbital with undisclosed providers whose standards and reputations are unknown to the public. In the case of Lockett’s execution, the latter drug was replaced with midazolam. The new drug failed catastrophically as a sedative. Inmates like Lockett are being executed with chemicals of unknown origins and untested effects.

Ironically, the extensive efforts of acquiring complex drug cocktails have caused more undue suffering than many conventional poisons would. It is an attempt to ease the consciences of the living that is causing executions to go wrong, and the system is simply unsustainable. If the 38 states that still impose capital punishment plan on continuing such policies in the upcoming decades, they will need to ensure that their methods place the human rights of the inmate over bureaucracy and politics.

We live in a country where we kill our worst criminals, and we do it in a manner that makes bullets to the heart seem humane. If states are to continue their policies of execution, they must establish high standards for transparency and oversight in the process, from the source of the drugs to ensuring their efficacy to the injection itself. Or perhaps the US should do what it should have done long ago—ban the practice of capital punishment once and for all.