Mr. Gorbachev, Tear Down These Bricks: Tetris and the Cold War

BY DAN BRAM

BY DAN BRAM

Let’s think, for a moment, about the popular culture of the American 80s. We were a culture of excess with much to spare: everyone wanted a piece of Americana, from South Africa to Czechoslovakia, Australia to Nicaragua. Ironically enough, one of the main cravers of American pop culture was our then-eternal nemesis—the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Underneath Stalin and Krushchev’s bombastic yawps against American culture grew an intricate and thriving black market for everything from the new Whitesnake album to bootleg Hollywood movies. The most famous example, perhaps, was mass imports of Soviet-banned blue jeans, which were seen as the quintessential symbol of American decadence. The great blue jean invasion eventually led to the Politburo negotiating with Levi Strauss to produce jeans in the USSR. Apparently communism was only immune to an ill-defined level of capitalist market demand.

But as any half-conscious observer of history knows, the Cold War was by no means a one-sided struggle. No, cultural exchange happened in both directions. And there is perhaps no better example of this “reverse” cultural imperialism than a small and simple piece of software developed by Alexey Pajitnov of the Academy of Sciences of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Concocted in a shadowy Moscow computer lab on Soviet-owned computers, it was the one thing I owned as a child in the 90s that my parents used to steal away from me when I went to bed to use for themselves. In Russian, it’s spelled Те́трис. In English, it’s pronounced Tetris.

Alexey Pajitnov, a bearded and whimsical software programmer at a time when many computers were still using punch cards, was a lowly developer at the Academy of Sciences of the USSR during the Cold War. Czar Peter the Great originally founded the Academy in 1724, then known as the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences, as part of the Enlightenment-era hip trend of the State as the main patron of both the arts and scientific progress. In Pajitnov’s time, the Academy somehow beat the odds and survived not only the Communist revolution, but also the ensuing decimation of free thought; the Academy of Sciences of the USSR was a rare oasis of intellectual curiosity and exploration under the shadow of the Iron Curtain. It employed physicists, chemists, biologists, and computer programmers—academics from every walk of scientific life. Their mandate was simple: explore, find out what the USSR didn’t yet understand (aside from nuisances like political freedom and free speech), and advance society. According to Pajitnov, “we were able to engage in everything quite freely, anything that interested us.” Pajitnov’s colleagues had won Nobel prizes in 1964 for the “maser laser principle” (imagine microwave-based lasers incinerating American shorelines) and in 1978 for their work in cyrophysics, which in a practical setting increased the overall output of the Soviet industrial machine. They had also calculated the effects of a hypothetical nuclear winter, as well as the trajectories of Sputnik satellites.

Pajitnov, lacking a pressing interest in the demonic politics of atomic threats, had developed a side project that translated a computer display’s letters into shapes, and allowed the user to control the movement of these new shapes. Back in that time, Soviets used the Electronika 60, a primitive personal computer that didn’t have the capability to display graphics. With the help of some of his colleagues at the Academy, Pajitnov took the traditional geometric puzzle game Pentomino, then a very popular pastime in the USSR, and translated it into a workable game on the Electronika 60. He called it Tetris, combining the Greek word “tetra” meaning four, and his favorite sport, tennis.

From there his game spread like a coked-out bubonic plague of euphoric proportions. Soviets loved it. Perhaps the main reason for its spread, though, was the USSR’s utter dearth of intellectual property laws. At the time everything on Soviet lands belonged to the Soviet government: machinery, cows, businesses, and debatably, souls. According to Mikhail Potyomkin, a programmer at the Moscow computer center at the time, “if we had tried [to sell the rights], then we would have ended up in prison.”

In 1988, Robert Stein, a business representative working with the United Kingdom-based software company Mirrorsoft, contacted Pajitnov to discuss obtaining the rights for Tetris. Stein was of Hungarian descent and had heard of the game through business contacts in his home country. Pajitnov agreed to discuss the matter further, and Stein took Alexey’s reply as a full license to produce the game. And that’s where the legal madness started.

Stein introduced the game to Jim Mackonochie, Mirrorsoft’s British founder, and the same addiction that had overtaken the USSR consumed the Brits as well. According to Mackonochie, “my wife and kids accuse [Tetris] of ruining the family Christmas because I found it addictive. But my wife found it addictive, and so did my two young kids.”

While Mackonochie was a rather crusty English businessman in the latter part of the 20th century, his experience turned out to transcend time, place, and status. I fondly remember family vacations to Myrtle Beach when I was all of 7 years old, riding along on the 14 hours from Indianapolis, Indiana to South Carolina in our family’s stereotypical suburban Toyota minivan. When we got to our condo my mom and sister would throw their bathing suits on, grab their towels and outright awful summer reading books, and run down to the beach. My father, however, was never a fan of the beach and would always complain about the tiny dry particles getting all over everything. If at 7 years old I had actually been a boy genius I would’ve jeered at his eremikophobia, but at the time I had more important concerns—namely getting him to drive me to the nearest convenient store to buy overpriced AA batteries for my dying turquoise Gameboy Color. It had a holographic peace sign sticker on the back that I had gotten from one of those gas station sticker machines so that everyone knew I was a socially-conscious peacenik, or maybe just someone who liked shiny things. I eventually convinced my father to play chauffer and take me to the store, but only because I employed one of the principle tenets of capitalism—the proposition of a mutually beneficial agreement.

In this case, my father was incurably addicted to Tetris. Getting the batteries for me wasn’t only the “thing you do” for your child, but it was also a means to get his own fix. He was a rabbi, and I remember countless times of walking into his office, Talmudic texts adorning the oak bookshelves, his congregationally provided laptop lit up with building and breaking Tetris blocks. At the beach, we were really just enablers: going to the coastal boundary of the United States was an excuse to hang out, tell stories, and get our Tetris fix.

Most families have cultural touch points that they try to share with each other, whether it be forced-viewings of Dennis the Menace, grandparents’ meatloaf recipes, or trying to explain the utter fear and hopelessness during the Cuban Missile Crisis to a generation who’s prime concern is the Saturday-morning cartoon schedule. But most of these transfers go from parent to child, and most of these transfers occur unsuccessfully. Tetris provided an opportunity for my parents to get legitimately involved in something I was interested in, and not in the way parents claim they’re super excited to see their third grader’s soccer game. Bold statement: no one cares about third grade soccer. Lots of people care about Tetris. When I would go to bed, I would leave my Gameboy at my bedside table. Just about every night during our beach vacations, I would hear a slight creaking noise as my door opened, and my mother or father commandeered the little turquoise box. I would wake up to find out I was 15 levels higher in Tetris. But how did that happen? And, perhaps more importantly, how did this happen night after night, trip after trip?

It turns out that video games are addicting. And I don’t mean addicting just to Caucasian suburban teenage boys who binge drink Redbull and never see the light of day. No, I mean they’re biologically addicting to the human brain—theoretically. Recent research at the University of Missouri—Columbia by Joseph Hilgard, Christopher Engelhardt, and Bruce Bartholow suggests that the constant action-reward system employed by many video games leads to increased stimulation in the brain’s pleasure center, in this case the nuclear accumbens (NAcc), which is part of the hypothalamus. However, Hilgard et al’s study was released in September 2013, and just a few months prior the American Psychiatrist Association (APA) rejected including video game addiction in the newest edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) due to a lack of conclusive evidence. Despite the scientific community’s tepidness in codifying video game addiction, it’s not hard to imagine any person from any demographic glued to a computer or Gameboy screen. It happens.

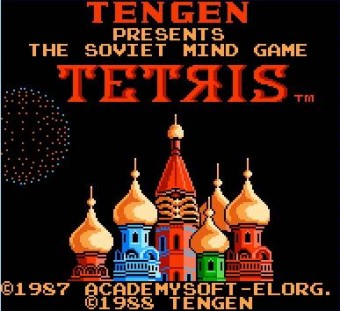

And addiction knows no borders. It turned out that not even ironclad Soviet border crossings could stop Tetris addiction from spreading outside the Soviet bloc and into the global community. Corporations in not only the United Kingdom, but also in the United States and Japan took a serious interest in obtaining the rights to produce Tetris. Mirrorsoft had produced a PC version of the game that was ready to launch globally. And in order to do so, they tapped into the American zeitgeist of an extreme interest in all things Soviet: things at least to be examined from a distance to avoid the glares of HUAC remnants. They packaged the game in Communist-red boxes, complete with daunting images of the Kremlin, Russian lettering, and daring taglines such as “it’s like Siberia, only harder.” Phil Adam, a representative of Mirrorsoft U.S., noted, “the curiosity of having anything from the other side of the Iron Curtain was kind of like memorabilia that people wanted to have.” In Mirrorsoft’s eyes it wasn’t just another puzzle game, but rather a glimpse into Soviet culture that Americans could enjoy safely from their La-Z-Boy’s. It was the Beatles playing rock ‘n’ roll in matching suits while standing relatively still. It was danger in safe packaging—and with huge profitability.

In order to make the most from their investment, Mirrorsoft approached Atari Games about producing a console version of the game, which they hoped to market heavily in the United States. But before anyone could make a move on anything, Mirrorsoft received a fax (or more specifically, an antiquated Telex) from an Orwellian Soviet agency called Elorg, informing them that they were producing the game illegally. Around the same time, a man named Hank Rogers, who worked for Bulletproof Software, found the game and was tasked by the videogame behemoth Nintendo to obtain the rights for a handheld version of Tetris for the lucrative, puzzle-obsessed Japanese market. It also should be noted that at the time Nintendo made up 70% of the world’s videogame market. Rogers contacted Robert Stein, who agreed to use his contacts in Moscow to secure the rights at a fee of $25,000.

Stein, however, stalled for weeks on his arrangement with Rogers, and eventually Rogers decided to take care of the matter himself and headed to Moscow without any contacts, prearranged meetings, or knowledge of how Soviet culture and society really operate. In an ironic turn of events, Stein headed to Moscow at the same time, and Mirrorsoft also sent Kevin Maxwell, son of British business magnate and Member of Parliament Robert Maxwell, to represent their interests. Three men looking for three licenses: handheld, console, and PC. If it sounds like a bad version of a “three men walk into a bar joke” it’s because it is, only with Cold War-era themes: multiple nationalities clashing, intense cloak and dagger game theory, and huge economic enterprises at risk.

But how could this happen? In a time when Siberian work camps were as common in Russia as idyllic summer camps were in America, when Red Dawn was seen as plausible material for a future documentary, when the Kremlin took sole ownership of every aspect of every citizen’s everyday life, how could a Soviet government agency possibly license a product to the highest bidder of three Western nations? And, perhaps more tellingly, how could the Soviets win in a situation that was inherently capitalist? How could these two systems mesh together?

It’s important to note that the creation of Tetris and its further distribution to the global market was by no means the only story of cooperation between the USSR and the West during the Cold War. In the 1950s, American and Soviet scientists developed the vaccine for polio using data and experiments from the other’s country. Under the auspices of the United Nations World Health Organization, the American-Soviet vaccine circulated around the world, and polio was decimated. Additionally, despite the fierce competition for space dominance, the United States and the USSR signed an agreement in 1962 to actually bolster joint research into exploring the stars. What separates the case of Tetris, however, is the level of cooperation. The deals that the corporations made weren’t the result of a grand Reagan speech, they didn’t involve mobilizing any tanks, and they didn’t involve either the CIA or the KGB. Rather, the fact that Tetris got out of the Soviet bloc at all was more a result of the coming culture change and Gorbachev’s desire for a better Russia. The Soviets had the real ability to throw Stein and Rogers in a Siberian gulag due to their respective copyright issues, but instead of signing their lives away, they signed distribution contracts. The Communists learned how to play the game.

And no player was better at it than the director of Elorg, Nikoli Belikov, a shrewd Soviet bureaucrat hell bent on not only upholding the appearance of Soviet domination, but also on securing the best possible deal for the Motherland. While he was not as well versed in Western business practices and negotiations as Stein, Rogers, or Maxwell, Belikov did have one ace up his sleeve—he was the only one who actually knew that all three men were seeking rights to Tetris. And he wanted to keep it that way.

He met with each man at separate times, using his staff to usher the businessmen around the building so that they never ran into each other. Stein recalled the experience with the eerie drama of a Tom Clancy book: “There was always a long corridor. They always keep you waiting in reception. No one talks to you. The chairs are uncomfortable. They lead you to a room always with a long conference table, like you’re being interrogated in court.” Belikov went through them one by one like a 80s movie villain interrogating his prisoners. He first ripped into Rogers for not having legitimate rights to the game. Then, in a separate meeting, he admonished Stein for failing to pay the royalties owed to the Soviet government for the game. He met with Maxwell last, and allowed Maxwell to make an offer on the rights. But Rogers had one trick left.

**

The end of the Cold War was a story of personalities as much as it was of nationalities. Despite my own utter enmity for President Ronald Reagan, which is possibly influenced by John Irving’s A Prayer for Owen Meany, the man had the gravitas to not only challenge Mr. Gorbachev to tear down the wall, but also to see it come down, brick by totalitarian brick. Likewise, Gorbachev saw the yearning in his people for a stronger voice in their own lives, whether in the streets of Leningrad, the tundra of northern Russia, or the committee halls of Moscow. Policies like glasnost and perestroika paved the way for a macro level thaw, and at the micro level, for people to connect in ways they never thought possible.

And this is where Rogers found his leverage point. Rogers met with Alexey Pajitnov on his own, and the two immediately hit it off. Pajitnov had never had the opportunity to talk with a fellow software designer, as the profession didn’t really exist in the USSR. Roger’s stories of international innovation, on top of his own personal charisma, sold Pajitnov on the rights going to Nintendo. Pajitnov went to his superior, Belikov, and told him that although Maxwell probably would offer more money, Rogers should get the rights because he was a good man and they could trust him. Belikov agreed, sent Maxwell home, and gave Rogers both the handheld and console rights.

The more interesting outcome, however, was with Stein’s fate. Belikov wrote up a new contract that denied Stein the PC rights he had already owned, and also enacted harsh financial penalties for the royalties that Elorg was owed. Belikov factored in Stein’s obsession with the backlogged royalty payments, hoping that he would not notice the usurped PC rights.

And it worked. Stein signed the final contract after haggling down the royalty payments, but because of his focus on that number, missed the clause negating PC rights. In short, the Communist beat the Capitalist at his own puzzling game. Whether or not this would have been possible a decade earlier, in harsher times and under a more stringent regime, is impossible to tell. What is clear is that the Soviets had not only grasped the concepts of capitalism, but had found a way to embrace them and excel in the confines of their own means.

The USSR got its money, Nintendo got its rights and sold the first Gameboy packaged with Tetris, and as was the case in the Soviet regime as a whole, the individual was left by the wayside. Alexey Pajitnov never saw another dime while Western companies and the Soviets worked together to make huge profits. Mirrorsoft’s Maxwell was so angered by the outcome that he called his father, who sent a Telex to Belikov threatening to raise the issue with President Gorbachev upon his arrival in London. Belikov, in turn, had real cause to fret, as Robert Maxwell had personally worked a deal with Gorbachev in the past to secure arms for the State of Israel. The two were buddies in a system where relationships were everything, and Belikov’s job, and in those times his personal freedom, was in jeopardy.

Maxwell eventually dropped the issue, as he realized that the parties involved were satisfied with their arrangements, and brining a qualm over a videogame to the President of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics probably wasn’t the wisest decision.

To date, Tetris has been released on more than 50 platforms in over 50 languages and played in over 185 countries—some of which don’t even exist today. It has sold more than 170 million copies, not including the thousands of unlicensed copies sold prior to solidifying the game’s rights. In comparison, the Halo series, perhaps one of the most successful videogames today, has sold just over 50 million copies worldwide. Bejeweled, a popular modern puzzle game, has sold just over 25 million copies, including downloads.

So why is Tetris still here? Why do people keep playing it? When I first played it, it was in the context of a fun pastime on my Gameboy. My parents, however, were around when its original, Soviet-imbued version hit the shelves. They were around when public schools played videos instructing students to duck under their rusting, wooden topped school desks to protect them from a 50 megaton RDS-220 hydrogen bomb—the Soviets called it their “Tsar Bomba.” To the older generation, Tetris is an eerie reminder of how lucky we are that we made it out of the 20th century how we did. Pajitnov’s contemporaries in the USSR were working on everything from training dogs to run towards tanks with bombs strapped to their bellies to suitcase nukes to mobile land-to-air lasers. But when the Russian Politburo finally adjourned in December 1991, it was Pajitnov and his universally simple work that continued to occupy the global consciousness—not the constant threat of nuclear disaster.