What I Learned in a Kenyan Protest

Recently I found myself locked in a shopping mall in the normally-bustling business district of Nairobi. The mall was teeming with large, grim-faced police carrying AK-47s and wearing combat fatigues. The heavy steel security gates had been pulled down and locked and the major street outside was eerily quiet. The bar was mostly empty save a few nonplussed locals and of course me.

I was walking to buy some lunch during a midday break in classes when I encountered a protest, a crowd of one or two hundred angry young men of the Les Miserablés flavor swinging pipes at the pavement, throwing stones, blowing vuvuzelas and shouting in English and Swahili, all the while ensuring that no cars could pass on the road. The students had been carrying on since about 9:30 that morning, angry as they were due to the apparent suspension of government-sponsored student loans.

Just as I had made my way through the thicket of humanity, I heard a rapid series of sharp pop-pop-popopops perhaps fifty yards behind me. I must admit here that I am a stranger to the diverse sounds of gunfire, so this cacophony was more than enough to inspire a quick dash into a nearby mall. The scene there was reminiscent of the film cliché so memorably redone in Raiders of the Lost Ark– I was the last person allowed through the fast-descending security gate, whose normally morose contingent of private security contractors were suddenly very alert.

From inside the locked and gated mall I could see very little. For the few dozen shoppers then locked into the three-story atrium of the building, life continued largely as normal. One must remember that the day before had been the two-year anniversary of the barbaric attack on Westgate Mall, a posh Nairobi shopping center turned hellish byproduct of radical Islamic madness. Put shortly, it takes a great deal to rattle the denizens of this city.

After some time, what little commotion had survived the first round of tear gas had completely settled and I decided to order some lunch. Suddenly I got a call from a professor: stay put, he said. The protest may have died down around me, but the students who had stayed behind in the classroom a few blocks away had had to lock the windows to stanch the rolling clouds of tear gas from the adjacent road, which in any event had been blocked by riot police. And so I hunkered down with my food and a potion, oh so courageously waiting out one installment in what can certainly be called Nairobi’s episodic political unrest.

When I tell people that I’ve gone to Nairobi for the semester, more often than not the reaction I get is one of concern. This is a dangerous place, I am told. Visitors here are robbed, kidnapped, murdered. That’s certainly not the impression I’ve gotten here, but perhaps my firsthand experience is inferior to the deep, reliable journalism promulgated by CNN.

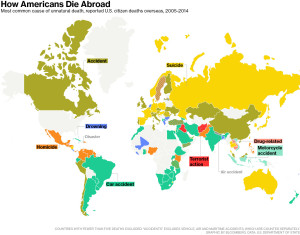

The reality is that in the vast majority of countries around the world, an American is more likely to meet his end in an automobile, motorcycle, aircraft, or other accident, or by suicide, modes of departure generally free of influence from nefarious brown people.

Even those countries whose names convey a sense of exoticism and danger are almost unfailingly deadly in the exact same ways St. Louis might be. Travelers to Egypt, for instance, need not fear jihadis unless they’re behind the wheel of a car; the most common threat to Americans there is the banal car collision, as it is in the international hub of Wahhabism, Saudi Arabia, and war-scarred Sudan. Even in Mali, a nation still recovering from a 2012 coup d’état and ongoing unrest in the Saharan north, Americans are more at risk from open water than from Tuareg militants.

One would do well to note the gender of the pronoun early in the last paragraph, as well: women are likely at much greater risk from those ugly creatures of the night who would do them harm, though that risk rapidly dissolves when one travels in groups, especially mixed-gender groups. Such is the rotten crust of life both abroad but also in ostensibly safe localities closer to home.

Allow me to stop short of recommending a family vacation to Khartoum – it’s just that the cautious American might be better off there than on the road in certain places in the States. Of course, there are exceptions to the maxim that conscientious travel abroad is safe. Countries like Somalia, Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria are best kept off one’s summer travel list, as are parts of countries where terror or crime run rampant, such as Kenya’s Garissa County and parts of northern Mexico.

That Mexico makes the list of dangerous countries is notable. Mexico is easily one of the most common spring break and summer destinations for Americans, and countless newlyweds have spent their blissful first week of marriage on the Yucatán and Baja peninsulas. Yet it’s not a complete weekly news cycle in the US without another assassination, kidnapping, brutal murder or epic drug bust within the borders of our Southern neighbor.

So what gives? In a word, irrationality. In another, ignorance. It would be unfair to attack Americans for their human disposition toward irrationality, and it should come as no surprise to the well-informed reader that our countrymen are distressingly ignorant of the world around them. One sympathetic Scot whom I met in a Nairobi bar patronized mostly by expatriates offered the explanation that in a country as vast and diverse as the US, no one should be surprised that only a third (a record high, by the way) of Americans even possess a passport, but to me that is unsatisfactory; having a passport is prerequisite neither to understanding Kenya’s security situation nor to the ability to find on a map any of the places we’ve leveled with guns and bombs.

In any event, international politics are complicated (five college classes on Africa later and I still have to think for a minute before I can say whether Robert Mugabe is from Zambia or Zimbabwe – thank the void that Zaire is no longer in play) and separate from the core question: why do Americans fear apparently war-torn Africa and not the cartel-riddled crimescape of Mexico and Latin America?

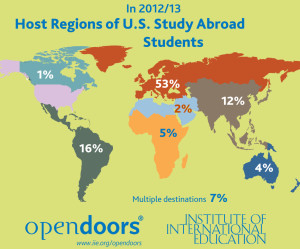

A retreat to the old whipping boys is in order – I blame the media! Our politicians are alarmists! Our schools are deplorable! But none of those answer my real question, which is that of why American college students specifically are so deplorably terrified of breaking out of their international and intercultural comfort zone. Being part of another country’s culture is a seductive proposition, but for some reason the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Spain, Italy, Germany and Denmark are more attractive destinations than those in the developing world. I’ve had it put to me that the average study abroad could be a fun and engaging and perhaps even transformative semester, but that only a handful of places can honestly be called life-changing. With limited experience in hand I have to agree.

On balance, the quality of a semester spent abroad is based on more than just locale. One could come to East Africa and spend all their time in a wealthy white suburb and get nothing from it; or they could go to Paris and live in a destitute immigrant neighborhood and render unrecognizable their worldview. Take my ruminations on countries, then, less as prescription and more a series of broad strokes.

In going abroad (perhaps in life), one should strive for difference. Going to the trouble of leaving the US for four months only to find oneself in a place scarcely different from whence they left seems to me an awful waste. Most only go abroad once – why not make the most of it? There will be ample opportunities later in life to tour the European capitals, and with a much heavier wallet to boot, but for most there is only a single chance to jump, probably flailing pathetically (as I have), into a wholly new cultural experience. That chance almost invariably vanishes after the close of one’s college career.

Now, for the concerned mothers at home, a word on safety, or more accurately a question followed by a collection of words: do you honestly think that any reputable American university, bound as they are by the onerous risk of lawsuits and negative shocks to the sanctified applicant pool, would incur even a modicum of danger by sending a student somewhere unsafe? Suffering a student casualty on an abroad program would be an utterly unprecedented blow to a school’s all-important ability to grant its students a credible guarantee of safety. The day that Washington University inaugurates a program in Mogadishu or Aleppo, two of the handful of places where journalists and aid workers are as a matter of fact abducted and worse, has not arrived, nor will it ever. Today more than in any prior academic generation, American academia has made risk aversion part of its credo, a trend manifest in the never-ending slew of invited and promptly disinvited campus speakers whose threatened presence has upset college students from sea to shining sea (Condoleezza Rice, Christine Lagarde, Common, Ayaan Hirsi Ali – and more locally, Phyllis Schlafly, Bristol Palin, Marvin Casey, David Horowitz and Scott Brown, come to mind). If university administrators are unwilling to allow their charges to be threatened even by words, how likely does it seem that the former would let the latter come under the existential threat of death or injury?

Conflict, be it ideological or cultural or physical, is the forebear of revelation. It was the stress of the American Civil War that brought Abraham Lincoln to the realization that emancipation was indeed a morally necessary cause and the horror of September 11th that awoke the US to the still-looming threat of violent Islamism. To alight purposefully in a culture that will assuredly clash with one’s own is perhaps the most powerfully transformative force one can confront, and it’s one that, given the financial and academic opportunity, everybody ought to.