The American West and the West Bank: Intersecting Histories of Settler Colonialism

Standing on the roof of an old fortress, my eyes focused on trying to make sense of the map being held up by our guide, resisting the wind threatening to carry it down onto the landscape it represented. It looked like the world’s ugliest pointillist portrait—a map of competing brown and blue dots: the first representing Palestinian cities—Bethlehem, Ramallah, Khalil (Hebron) and countless small villages, and the latter showing the location of Israeli settlements, their roofs creating a patchwork quilt below our vantage point.

“It’s only getting worse,” our guide told us. He was a volunteer for the left-leaning Israeli organization Peace Now, which advocates for the fulfillment of a two-state solution. Believing that the continued creation of settlements in the West Bank is the biggest threat to the establishment of a viable Palestinian state, their initiative Settlement Watch uses research, analysis, and advocacy to expose and protest settlement expansion. One part of that effort is educating Americans like myself, traveling with a cohort of university students as part of a dialogue and leadership program, on the reality of what “settlement expansion” looks like. A drive through the hills of the West Bank, matching dots on the map to the land under our feet, quickly dispelled the popular image of a few roughly-constructed homes on the edge of a sparse landscape, manned by a couple of rogue individuals, quietly living out their lives.

“Israeli settlements are planned construction projects staked out on top of ancient olive groves, whose cultivators would never enter the building now suffocating their roots.”

Israeli settlements are neighborhoods, villages and towns created out of solid cement, cinderblock, and pavement, protected by barbed wire fences and Israel Defense Forces (IDF) soldiers armed with big guns. They are planned construction projects staked out on top of ancient olive groves, whose cultivators would never enter the building now suffocating their roots. They’re what should be a twenty-minute drive turning into an hour and a half because of road infrastructure being illogically obstructed, while settlers use Jewish-only roads to access Jerusalem, which is prohibited for Palestinians without permits. They’re the plans for the creation of Israeli houses that would disconnect Palestinian East Jerusalem from the rest of the West Bank. The creation of “security concerns” that are used as an excuse for militant surveillance and harassment of Palestinians trying their best to find a semblance of normalcy in the continued humiliations of occupation. They’re the goal of making life in the West Bank so unbearable, that maybe they would just leave and never come back.

Though the trauma of occupation can’t be reduced to numbers, all of this amounts to at least 132 settlements breaking up any possibility of a contiguous state in what is left of historical Palestine. This is not including the 121 “outposts”—settlements not formally recognized by the Israeli government, but that somehow still find a way to be connected to the electricity grid or water source. The reality of settlements is, as of January 2019, 413,400 Israeli citizens (excluding East Jerusalem) whose removal, in the event of the creation of a Palestinian state, sounds more like fantasy than solution. Tens of thousands of families whose government gave them permission and encouragement to create homes out of land that was never theirs to claim and that the international community has called a violation of international law for decades.

Until last week, the United States has shared that stance with allies and international institutions such as the United Nations and the International Court of Justice, however contradictory it was to its material support of the Israeli occupation. But on Monday, November 18th, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo changed the United States’ position, stating that settlements in the West Bank did not violate international law. While the decision was a sudden reversal in long-standing policy, and disheartening to those demanding the end of occupation, it would be naïve to see it as a complete shock. Pompeo’s announcement stood in line with a long history of the United States supporting Israel politically and militarily, as well as with the Trump’s administration’s more recent support of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who has struggled to form a government after two rounds of very close elections. Over the course of these elections, Netanyahu has declared intentions to formally annex the West Bank, which Israel has illegally occupied since winning the 1967 war. The result would be the formalization of what many already consider to be an apartheid state, and the death of hope for Palestinian self-determination, liberty, or nationhood.

“The United States condoning illegal settlement creation should be unsurprising for a deeper reason: its own long history of violent and unacknowledged settler colonialism.”

However, the United States condoning illegal settlement creation should be unsurprising for a deeper reason: its own long history of violent and unacknowledged settler colonialism. It is this history of genocide and forced displacement that lies at the core of the United States’ inability to hold Israel, which similarly touts a narrative of national exceptionalism as the “only democracy in the Middle East,” accountable for its actions. How can the United States effectively call out land-grabbing in the West Bank, when it has barely acknowledged the stolen land under its capitol building? How can the United States critique Israel for illegal settlements, when Israel can point at the copies of Little House on the Prairie lining American classroom shelves?

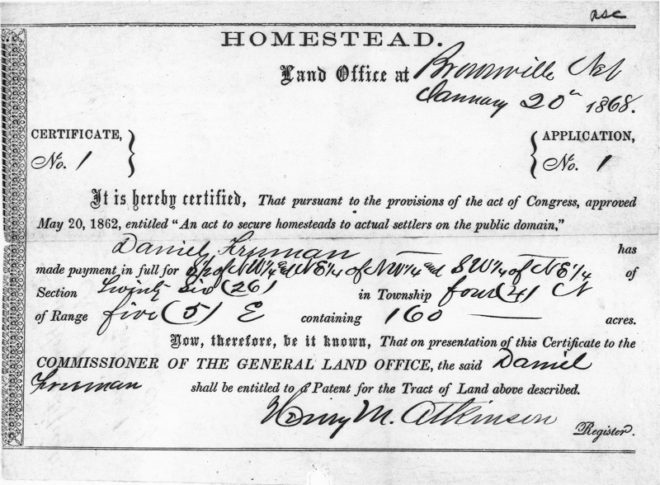

On May 20, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln passed the Homestead Act into law, marking a new phase of expansion into the American West. For the cost of a small registration fee, the law provided American citizens with 160 acres of “public land” on the condition that they lived on it, and “improved” it through the creation of a successful farm within five years. By 1934, Anglo-Americans had taken over 270 million acres of land, belonging to various native nations, into private ownership. This went hand-in-hand with a lesser-known piece of legislation called the Dawes Act, which broke up Native American reservation land into private lots headed by nuclear families, forcibly subdividing communal property and facilitating more land seizure.

The parallels that can be drawn between the settlement of the American West and of the West Bank, though obviously separated by a hundred years of history and cultural context, are striking. In both, a disproportionately powerful and militarized government facilitated its citizens in systematically displacing another group, deemed racially and culturally inferior. Both processes of occupation were sustained through military might, in the form of IDF soldiers in the West Bank and American regiments stationed at forts along the Western frontier. In both cases, individual settlers were incentivized through a combination of economic and ideological motivations. The farmers of the 1860s sought subsidized farmland, and many Israelis settlers seek cheap, government subsidized housing within the West Bank. Some in both cases believed they were settling land destined to them by God.

Making visible these shared histories of violent nation-state building is not an excuse or a justification for the United States continuing to facilitate the destruction of Palestinian land and lives. The reflection of the violence of 19th century American settler colonialism within Palestine should act as a site of critical self-reflection and action—both here, and there. As a country, we must stop teaching our history of displacement, murder, and cultural erasure as one of brave exploration and pioneering spirit. We must critically examine the ways that settler colonialism lives on in forms much subtler than the Homestead Act—through continued resource extraction on Native lands, abuse of Native women, and the criminalization of Native resistance. At the same time, we must speak out against the ways we carry the legacy of our own unaddressed history into our foreign policy, supporting a 52-year old illegal occupation and even longer project of ethnic cleansing.

No matter what international law or the Secretary of State says, what is happening in Palestine should be a source of shame and moral outrage for any country that claims to stand for democracy and justice. As the citizens of a country that has built its international moral capital through claiming those ideals, we have the obligation to demand and do more—both for the indigenous communities whose stolen land we stand on, and for the Palestinians whose land we are watching being stolen as we stay silent.