Finding a Filibuster that Works

Ever since its inception, the filibuster has been the subject of criticism and concern. However, despite concerns that the bill-blocking tactic is a simple manipulation of procedure, most had viewed the filibuster as a consensus building tool in the spirit of our governments founding. (Remember all that cool stuff about separation of powers and checks and balances that we learned in fourth grade?). But in the aftermath of the health care debate, the filibuster has come under attack by a wide range of commentators, notably Paul Krugman of the New York Times and Ezra Klein of the Washington Post. The focus of these critiques is that the health care bill highlights the damaging nature of the filibuster; senators can hold legislation hostage and prevent any government action. According to these critics, by requiring 60 votes to close debate (and in doing so essentially requiring 60 votes to pass a bill), the filibuster raises the required level of support to an unnatural, virtually unobtainable level. To bolster their argument, the anti-filibuster advocates point to the fact that the Democrats hold the largest majority either Party has possessed in decades, yet because of the filibuster the vast majority of their legislative priorities are held in stasis. If this procedural rule inhibits government from taking action and serving the people, then it needs to be eliminated.

Ever since its inception, the filibuster has been the subject of criticism and concern. However, despite concerns that the bill-blocking tactic is a simple manipulation of procedure, most had viewed the filibuster as a consensus building tool in the spirit of our governments founding. (Remember all that cool stuff about separation of powers and checks and balances that we learned in fourth grade?). But in the aftermath of the health care debate, the filibuster has come under attack by a wide range of commentators, notably Paul Krugman of the New York Times and Ezra Klein of the Washington Post. The focus of these critiques is that the health care bill highlights the damaging nature of the filibuster; senators can hold legislation hostage and prevent any government action. According to these critics, by requiring 60 votes to close debate (and in doing so essentially requiring 60 votes to pass a bill), the filibuster raises the required level of support to an unnatural, virtually unobtainable level. To bolster their argument, the anti-filibuster advocates point to the fact that the Democrats hold the largest majority either Party has possessed in decades, yet because of the filibuster the vast majority of their legislative priorities are held in stasis. If this procedural rule inhibits government from taking action and serving the people, then it needs to be eliminated.

However, there are reasonable rebuttals to this argument. As previously stated, the filibuster acts in agreement with the basic principles of American government. The structure of our government was created to prevent hasty action and easy access to excessive power. The filibuster acts as a check, ensuring that any Senate majority cannot shove throw whatever legislation it wants without consulting the minority, examining public opinion, or even considering the ramifications of their actions. Similarly, the filibuster acts as a consensus building mechanism; by requiring 60 votes to close debate, the filibuster requires that the majority work with the minority, and craft a bill that takes a variety of viewpoints into consideration. With this wide range of opinions, isn’t the best result most likely to emerge?

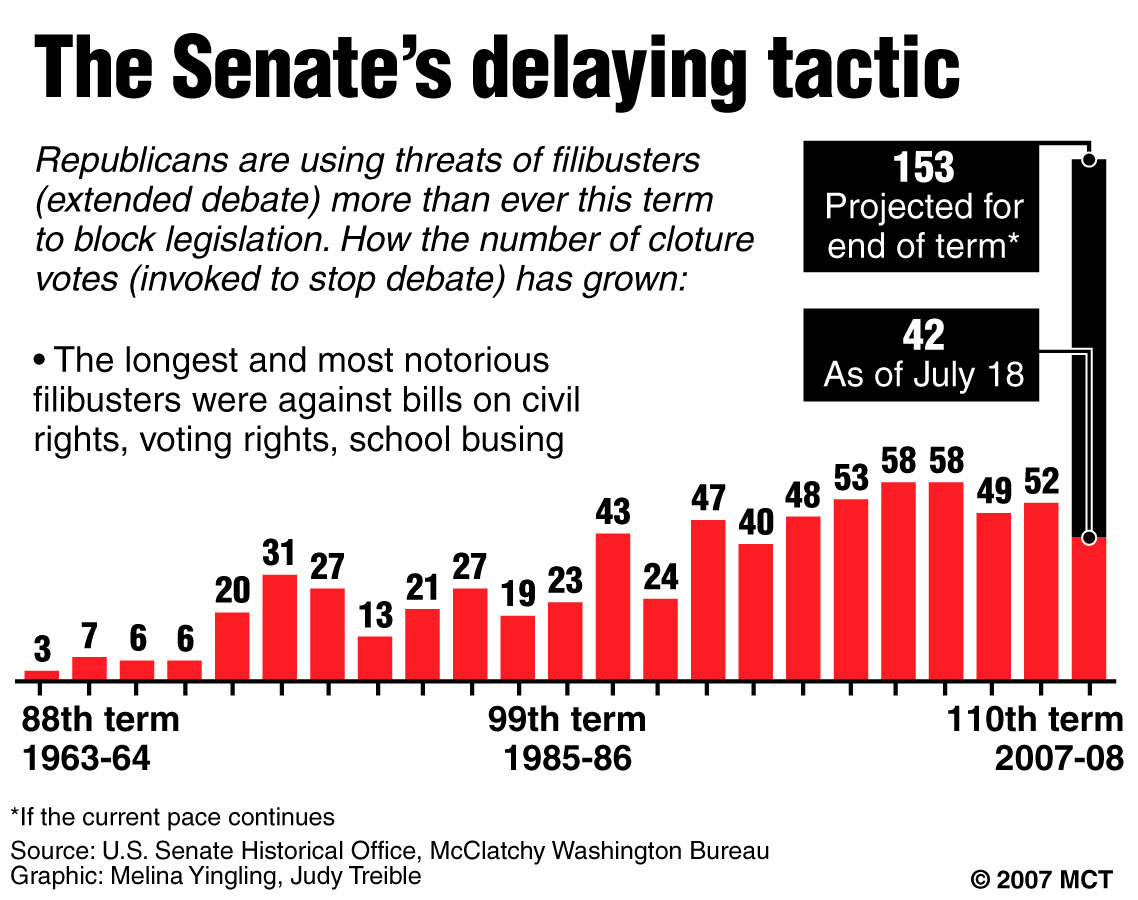

The problem with this defense of the filibuster is that it presumes that both the majority and the minority are interested in taking action, even if their vision of what policies we should enact differ. Currently, however, the strategy of the minority party is simply to obstruct as much as possible, and prevent anything from happening. While this has been a tactic used by both Democrats and Republicans since the Speakership of Newt Gingrich, it has occurred to an absurd degree in the last year. Not only has this caused increased tensions in the Senate, it has also turned the filibuster into a tool for abuse rather than consensus building. While 50 years ago the filibuster was only used on 8% of legislation, this decade it is employed 70% of the time (which again shows that this is a problem caused by both parties). The filibuster could be an excellent means of achieving moderation and pushing legislators to find common ground. But when the main goal of lawmakers becomes trying to prevent the government from doing anything, the filibuster is too strong a tool of obstruction. That is the culture of Washington now, and that means the 60-vote filibuster must be brought to an end.

However, to entirely eliminate the filibuster would be a poor choice. While the current model does not work, removing all extra burdens to the passage of legislation goes too far, and would likely lead to radical policy shifts with each successive election. As appalled as outspoken liberals such as Krugman and Klein are by the current procedural structure of the Senate, they would likely be even more irked if the Republicans could have passed whatever they wanted back when they had a razor-thin 51-49 majority earlier in the decade. The best solution is to find a middle ground; the filibuster should not be eliminated, but rather weakened so that it can continue to require consensus without being an easy method of obstructing all legislation. If, for example, a 55 vote majority were required to close debate, then it would still require consensus beyond a simple majority and foster compromise, but would allow the Senate to function without obstructionists holding a trump card that can be used on every piece of legislation the body sees.

However, to entirely eliminate the filibuster would be a poor choice. While the current model does not work, removing all extra burdens to the passage of legislation goes too far, and would likely lead to radical policy shifts with each successive election. As appalled as outspoken liberals such as Krugman and Klein are by the current procedural structure of the Senate, they would likely be even more irked if the Republicans could have passed whatever they wanted back when they had a razor-thin 51-49 majority earlier in the decade. The best solution is to find a middle ground; the filibuster should not be eliminated, but rather weakened so that it can continue to require consensus without being an easy method of obstructing all legislation. If, for example, a 55 vote majority were required to close debate, then it would still require consensus beyond a simple majority and foster compromise, but would allow the Senate to function without obstructionists holding a trump card that can be used on every piece of legislation the body sees.

Finally, while the filibuster does appear to be in need of reform, there is a greater point to take from this issue. We can improve efficiency in Washington and make government more effective, but so long as obstruction is the best strategy for the minority party, we will never have a truly effective government. Our lawmakers need to move past this culture of obstruction, and if they cannot the voters need to go to show them we will no longer accept it. Perhaps it is time we did not simply look to results, but also to effort. I’ll discuss this topic and how we can affect this flawed obstructionist culture in my next online column.