The year 2024 has been marked by unprecedented events in U.S. history, including the assassination attempt on former President Donald Trump, the lingering consequences of the January 6th attack, and President Joe Biden’s unexpected withdrawal from the race. Yet, amidst these drastic events, one element has remained unchanged in every American election for the past 236 years: the Electoral College. As society evolves and the political landscape transforms, the question arises whether the Electoral College still serves as the best method for ensuring a fair and representative modern democracy. According to Alexander Hamilton in Federalist Paper Number 68, the Electoral College was created by the framers as “a compromise at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia between large and small states.” At the time, there was fear that populous states such as Massachusetts, New York, Pennsylvania, and Virginia would be the sole decision-makers for the presidency, which is why The Great Compromise was created at the Constitutional Convention of 1787. This gave each state an equal number of senators regardless of population while linking representation in the House of Representatives to population size to appease both small and large states. The Electoral College has functioned well for most elections, but the fact that Donald Trump lost the popular vote to Hillary Clinton by over 2.8 million votes but still won the presidency with 74 more Electoral College votes in the 2016 election prompts a reassessment of whether this system should remain.

The Electoral College was born amidst much debate grounded in reasons that continue to influence discussions about its relevance today. The main argument in favor of the Electoral College is that it ensures all states have a voice in the election process and protects smaller states from being overlooked by the majority, however, it may not work as intended. In theory, the Electoral College requires presidential candidates to gain widespread support across diverse regions, which prevents heavily populated urban areas from dominating national elections. This aims to promote national unity and give less populous states a greater influence in the electoral process. However, despite the intended benefits, the system often falls short in practice, as it may not always reflect the true will of the people.

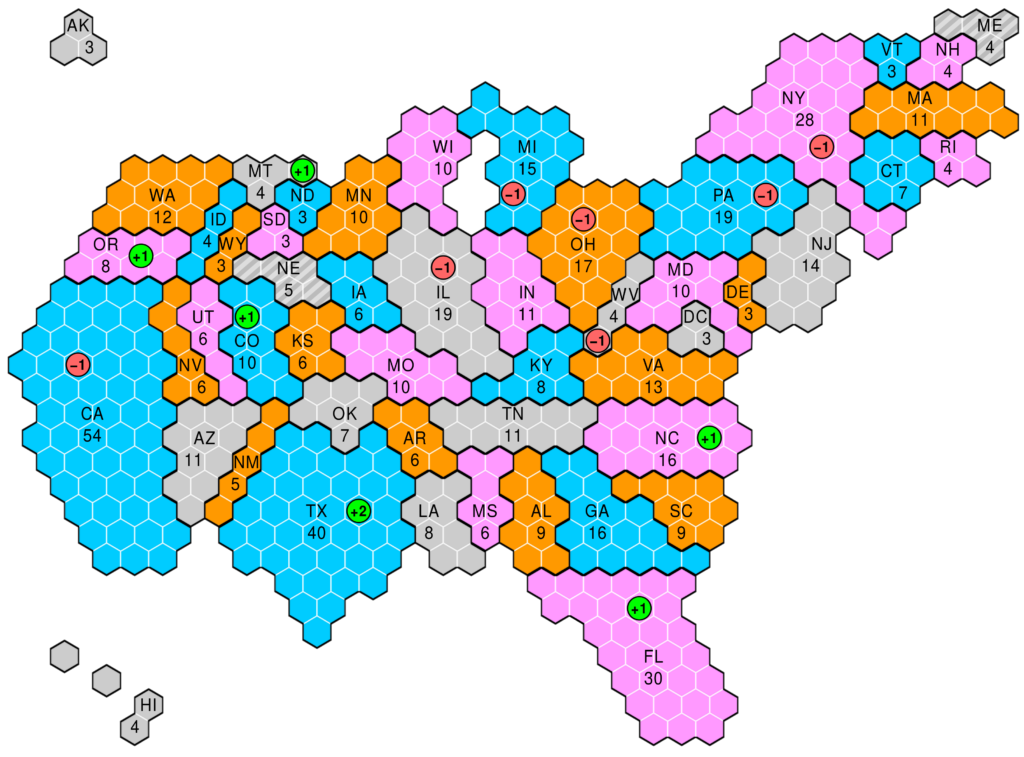

While the rationale behind the Electoral College made sense in 1788, changing times call for a reevaluation of its effectiveness and relevance today. One key argument against the system is that it gives disproportionate power to swing states, allowing a small number of states to determine the outcome of presidential elections. This undermines the democratic principle of “one person, one vote,” as the influence of voters in battleground states is significantly greater than that of voters in states perceived as solidly red or blue. Additionally, it is argued that presidential electors, who are responsible for casting the deciding votes, are no more qualified than the general public to make such a crucial decision. While many states legally require electors to vote in line with the popular vote, not all states have such laws, leaving room for unfaithful electors to potentially disregard the will of the people. This inconsistency, combined with the fact that a small group of individuals hold the power to override the collective choice of voters, further underscores the flaws of the Electoral College and strengthens the case for its removal. In Stanford Magazine, Jack Rakove, a professor of political science, highlights this concern by stating, “Having the states play an autonomous role in presidential elections, it is said, reinforces the division of governing authority between the nation and the states. But explaining exactly how it does this remains a mystery.” As a result, the system is often seen as outdated and misaligned with contemporary democratic values. Additionally, according to Pew Research Center, “more than six-in-ten Americans (63%) would instead prefer to see the winner of the presidential election be the person who wins the most votes nationally. Roughly a third (35%) favor retaining the Electoral College system.” This disconnect between public opinion and the current system suggests a need for reform to ensure that the government truly reflects the desires of its citizens.

The debate over the Electoral College continues to evoke strong opinions, largely opposing the system. While its defenders highlight the importance of protecting minority voices and maintaining the federalist structure of the nation, critics argue that the system no longer aligns with contemporary expectations of representation. The 2016 election and growing public dissatisfaction have intensified the need for change, with many Americans favoring a direct national vote for the presidency. As society evolves, it is crucial to reflect and reconsider whether the Electoral College remains in the best interest of the people, or if a more democratic system is needed to uphold the principles of representation and equality.

Kyra Meyer ‘27 studies in the College of Arts & Sciences. She can be reached at k.l.meyer@wustl.edu.